Seeing Double: Amherst’s $2.4 Billion Question

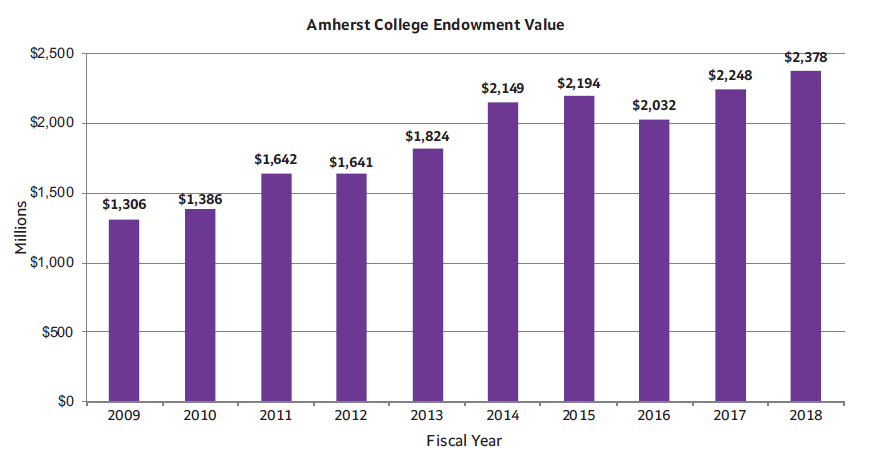

While Amherst students have spent the last few years studying, learning and debating which mascot should go on the mugs at AJ Hastings, the college’s endowment has been quietly exploding. In 1998, Amherst’s endowment stood at $528 million. In the following decade, the college doubled this hardly insubstantial sum, expanding the endowment to about $1.3 billion by 2009, according to the Amherst Financial Report. Over the past 10 years, that growth has continued. Last year, the college announced a 10.1 percent return on the endowment, placing it at the truly ludicrous total of nearly $2.4 billion, a sum larger than the GDPs of 25 countries, according to the World Bank.

Students might reasonably expect the school to have used a substantial portion of this cash influx to create and improve life for students, staff or faculty. Instead, according to the college’s annual financial report in 2018, Amherst has reduced the annual growth of its budget from a growth rate of 7.3 percent in 2014 to just 3.6 percent in 2018.

The school has consistently drawn the same percentage of cash from the endowment, while income from student fees increased 36 percent in the last decade. Amherst’s current policy is based around drawing a steady and moderate stream of income from its endowment investments, but the sums pouring into its coffers are anything but moderate.

Higher education experts sometimes claim that endowment funds are frozen and can’t be used for anything other than a few specific purposes, but that isn’t true at Amherst. In 2017, financial statements show that $672,096,986 of the endowment, or about 30 percent of its total, was unrestricted, and within certain limitations, most of the rest was also tappable. Only 20.3 percent of the endowment was completely frozen.

The American Council on Education, the nation’s primary higher education association, suggests that colleges maintain at most a 3 percent growth in its annual endowment (before inflation) and spend the extra money. That way, colleges can save up for recessions, while also tending to their campus’ present needs. In the long term, this policy is designed to result in modest endowment growth. However, in the past 10 years, Amherst has instead allowed the endowment to grow at a rate of over 6 percent per year. Clearly, Amherst is not spending enough of its endowment revenue.

In 2008, Amherst’s last president, Tony Marx, argued in an op-ed in the Los Angeles Times that Amherst needs to continue to invest aggressively and save money. The endowment needs to grow, Marx wrote, so that in the event of a market collapse such as the 2008 recession, Amherst would continue to retain the ability to spend money to help students.

True, Amherst’s endowment lost $400 million during the financial crisis, but instead of investing less in the stock market, Amherst’s policy has been to double down in order to compensate for the next potential recession — never mind the fact that a large endowment does little good for the college simply by existing and not being used. Arguing that the endowment needs to be invested in order to prevent future losses from investment is a counterintuitive approach.

Marx also argued that wealthy colleges like Amherst lack useful ways to spend extra money, a point even more indefensible than his first. According to the Chronicle of Higher Education, full-time Amherst professors are paid, on average, just 68 percent as much as their counterparts at Harvard, and 72 percent as much as those at Yale. When adjusted for inflation, Amherst professor salaries have actually decreased over the last 10 years. At the same time, student fees have skyrocketed. Amherst’s sticker price rose by an average of 4.2 percent per year in the last decade, far outpacing inflation. Plus, the campus will have to devote substantial funds to its goal of achieving carbon neutrality by 2030. In short, Amherst has plenty of productive uses for its surplus funds.

All of this penny-pinching comes at a time of great symbolic importance for the college. “Promise: The Campaign for the 3rd Century” is an ambitious program which gave us a new science center, new campus facilities and more faculty positions in STEM departments. The problem is that none of these improvements are actually paid for by Amherst. Using the “Promise” campaign as its justification, Amherst has spent the last few years soliciting donations from wealthy alumni. Millions of dollars in donations just in the last two years, for instance, have more than offset the cost of the Science Center in full. This has removed the burden of responsibility from the endowment to the alums and raises the question of why alumni should donate to projects if the money only services the growth of the endowment.

Instead of investing virtually all of its endowment in the stocks of huge corporations (many of which have controversial practices involving the environment and human rights), it’s time Amherst lives up to its own promise and invest its endowment in what should be its highest priority: its community.

Last year, if Amherst had kept 3 percent of its endowment growth instead of 5.7 percent, it would have added $60.7 million to its operating budget. Instead, Amherst made $66.9 million from student fees last year, as stated in the financial report. Had Amherst allocated all its new endowment money towards financial aid, the vast majority of students wouldn’t have paid a cent for tuition. Financial aid might not be the best use for all the extra cash, but it is one example of the endowment’s potential to improve the community.

If Amherst started tapping into its resources at a more reasonable rate, it could offer vastly better financial aid and services than even Harvard and Yale. Our acceptance rate would plummet (to the joy of those who care about such things) and other elite schools would face pressure to imitate our model, if only to compete for numbers, top students and professors.

This strategy wouldn’t harm finances in the long term either. The endowment would continue to grow through the current investments, and in the meantime Amherst would be giving its students the tools to be more successful than ever before. With a better-resourced education and less debt, Amherst students would thrive and more willingly show their appreciation to their alma mater. Amherst already makes tens of millions every year from alumni donations. Imagine how much stronger Amherst’s base of alumni support would be if Amherst did an even better job to prepare students for their careers.

Amherst is uniquely positioned to take a leadership position on ethical endowment policy. We have one of the largest per-student endowments in the country, and our endowment rules are less restrictive than other institutions. We have the ability to make our college a better institution by investing in the community rather than outside corporations.

The value of an academic institution comes not from how much money it has saved, but from how well its money gets spent. The endowment is not just a means to save for the future. Amherst students are the future of the college, and investing in us is a better bet than investing in Wall Street.

To find out more about Amherst’s financial priorities, see the Annual Financial Report available online.

Comments ()