Seeing Double: Amherst’s Invisible Financial Aid Crisis (Part One)

As we write, one of us is on track to graduate from Amherst College with $135,000 in student loan debt. The other will graduate with $27,000 of debt in his name and $110,000 in his parents’. And we aren’t alone: 28 percent of graduates in the class of 2019 had student loans averaging $22,629, according to Amherst’s 2019 Common Data Set. That debt casts a dark shadow over our futures and is a source of tremendous worry for us and our families. It’s all the more galling that we’ve accumulated this debt in order to afford a college that purports to have one of the best financial aid systems in the country. A college that, in the words of admissions officers, “makes a college education affordable.”

At Amherst, it isn’t common to talk about financial aid or debt — it’s seen as a personal matter, hard to hear about and even harder to bring up. The huge range of wealth among students doesn’t make it easier either. Our silence persists despite, or perhaps because of, the enormous impact that debt has on students.

But when we shy away from talking about our struggles paying for college, we let the problem fester. Those who take on debt suffer in silence, and those who don’t stay oblivious to the problem. Without schoolwide data, it’s hard to argue when Amherst says that it has one of the world’s finest financial aid programs, and those of us with debt problems often assume that we’re alone in our struggles.

Even if Amherst possesses one of the best aid programs in the country, it isn’t exempt from scrutiny or criticism. Any amount of error is too much when it comes to financial aid. Too often, students buy into elite colleges’ assurances of affordability only to find themselves encumbered by crippling debt. This week and next, Seeing Double will examine Amherst’s financial aid system and assess whether Amherst is living up to its promise of affordability.

The first of Amherst’s boldest financial aid promises is its relatively new “no-loan policy.” On its website, Amherst proclaims, “in our financial aid packages, we’ve replaced all loans with scholarship grants, making Amherst one of the few colleges and universities in the country that do not require students to take on student loans.”

A less-than-charitable pair of columnists might point out that Amherst’s proud statement is grossly misleading because Amherst evidently does require loans — neither of us could pay our tuition without taking on debt. A so-called no-loan policy doesn’t solve the debt problem. It just deflects blame.

First of all, Amherst does issue loans to students; they just aren’t offered initially. The class of 2019 owed Amherst College $128,000 in institutional loans when they graduated. Moreover, Amherst’s reluctance to initially package loans in financial aid offers doesn’t decrease debt. Rather than receiving loans in our financial aid packages, we’re forced to seek them out ourselves. Amherst’s suggestion that the no-loan policy allows students to graduate debt-free is misleading at best and dishonest at worst.

We say it’s dishonest because the no-loan policy has done nothing to prevent the debt crisis from growing. Although the percentage of graduates who borrow has declined from 43 percent in 2006 to 28 percent in 2019, the amount of debt carried by the average borrower has almost doubled from $11,626 to $22,629. That means that while the total amount of debt in each graduating class has slightly increased, the number of students who have to carry that burden has shrunk — so for those who do carry it, the burden has ballooned. Fewer students in debt mean less public outcry and better numbers for Amherst, but when graduating students owe roughly twice as much as 15 years ago, the problem is more urgent than ever.

Let’s set aside the no-loan policy and talk about another of Amherst’s claims to fame: meeting 100 percent of demonstrated financial need. It’s the first phrase you see on the Office of Financial Aid’s website, and if you’ve ever been to an Amherst financial aid info session, you’ve heard someone say these words. Closer examination reveals that meeting all demonstrated need is a deeply flawed system for giving out financial aid. What exactly is “demonstrated need?” Does a family “need” to be free of debt after college? Apparently not, given Amherst students’ borrowing rates.

Across schools that claim to meet all need, financial aid awards appear highly arbitrary. To test the consistency of these schools, we plugged Carl, our fictional middle-class friend, into the financial aid calculators of over a dozen leading colleges. The results varied, sometimes shockingly so: while Amherst determined that Carl could afford to pay $113,300 over four years, Colby College decided that the maximum Carl could afford was $66,800. (Unsurprisingly, Carl is now a passionate Colby Mule.) Though the differences between Amherst and other colleges were smaller, they often exceeded $10,000. If the policy of meeting all needs were objective, every college would offer the same package to the same person.

In short, promising to meet all demonstrated financial need is not a promise to make college objectively affordable. It is a promise to abide by Amherst College’s definition of what’s affordable, which is no promise at all. When judging the effectiveness of financial aid, we shouldn’t take into account what the college promises to do. Instead, we should inspect student outcomes. Though Amherst isn’t alone in graduating students with debt, some of its peers are much better at keeping that debt low.

To illustrate this point, we’ve plotted each NESCAC and Ivy League school according to its per-student endowment value and average student debt at graduation. Traditionally, a college’s per-student endowment is seen as a rough measure of its financial resources.

As shown in the graph, our college has a higher per-student endowment than all but Harvard, Yale and Princeton, but graduates students with more debt than Williams and the University of Pennsylvania. And other colleges — including some that are far less wealthy than Amherst — have only slightly worse outcomes for students.

Next, take a look at the trendline, which tells us what to expect for a college’s average student debt at graduation given its resources. Measuring to the right along the horizontal axis, you can see that Amherst graduates have thousands more in debt than might be expected. By this metric, Amherst’s performance is worse than any of its peers but Dartmouth.

Of course, each of these schools admits a different student body with different financial backgrounds — if a school only admits rich students, it probably doesn’t generate much student debt. This scatter plot isn’t an all-encompassing metric with which to gauge schools, but it does show us one thing: among elite colleges, Amherst isn’t particularly good at graduating students without debt. And considering its resources, one could reasonably expect it to do better.

Now, let’s cast our net even smaller and compare Amherst with its arch-nemesis: Williams College. Both on the football field and in financial aid, Williams has us beat.

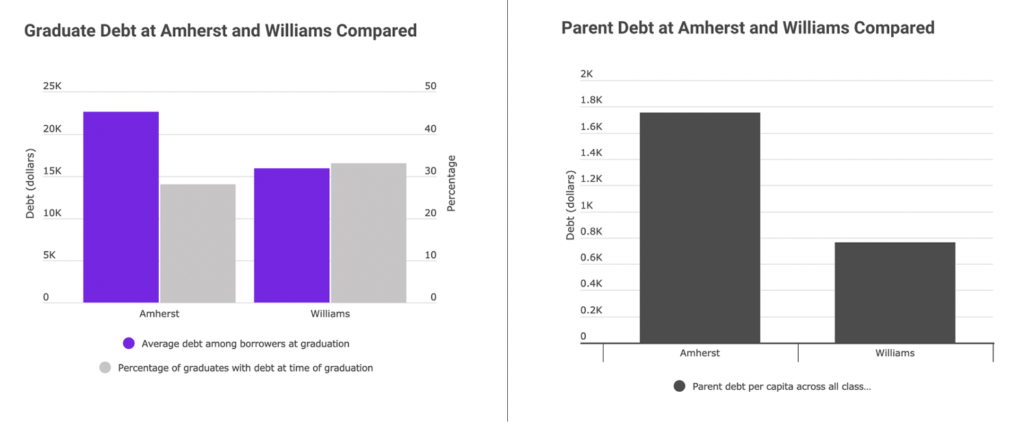

In the class of 2019, about one third of Amherst and Williams students graduated with student debt. On average, Amherst borrowers owed more than $22,000 at graduation while Williams borrowers owed only $16,000. In other words, Amherst graduates who borrow have almost 50 percent more student loan debt than their rivals at Williams. Moreover, Amherst student debt is four times more likely to be private rather than federal, and private debt is much worse for students.

This isn’t an apples-to-oranges comparison: Amherst and Williams could swap student bodies and be virtually unchanged in every metric we could find, including socio-economic status, race, gender and geographic location. We won’t say that our rivalry with Williams is just highly disguised self-hatred, but we will say that Amherst students look almost exactly like their counterparts at Williams. The schools even spend the same amount on financial aid per student. Yet Amherst’s outcomes are far worse.

In truth, we don’t know why Amherst fails its students so much more than Williams, but we suspect it has something to do with school policy. Amherst and Williams take roughly the same students and spend the same money on them, yet Amherst loads them with much more debt. The only conclusion is that something is going wrong with Amherst’s financial aid.

Part of the discrepancy might lie in Amherst’s external aid policy, which is how it deals with money from outside sources like National Merit or Kiwanis. Excluding work-study, only Williams allows students to pay part of their tuition with external scholarships. Amherst students get virtually nothing from them. That could explain why Williams students declare about twice as much in external scholarships as Amherst students: $2.9 million vs $1.5 million. Since external scholarships actually benefit Williams students, they’re likely much more eager to seek them out. This difference in policy might partially explain the schools’ debt gap.

However, there’s probably more going on than just different ways of handling external aid. Because of the secretive nature of financial aid, it’s not easy to assess what might be going wrong. Even so, as anyone who’s on aid can tell you, the Office of Financial Aid makes inexplicable decisions. Last year, one of us owed $6,000 more in tuition because it looked like one of his parents suddenly owned two houses when they really owned just one. The other had to borrow thousands extra because Amherst counted money his parents borrowed as income.

Other failings are broader: Amherst initially refused to pay for international students’ travel expenses after the campus shutdown. We’re powerless to speculate how many other students have been blindsided like this, but Amherst’s incomprehensible financial aid decisions must contribute to its higher-than-expected levels of student debt.

The whole problem gets even worse when you realize that lots of student debt isn’t reported in the numbers we’ve presented. For example, Amherst’s website proudly states that “72 percent of students graduate debt free.” This fact, although true, misrepresents the situation. In general, students don’t pay for college. Parents do.

Only by digging through dusty records can the investigator discover that, in 2019, parents of current Amherst students took on over $3.3 million in student loans. Lest you think that these sorts of numbers are inevitable, take a look at Yale, where the total parent debt generated was exactly $0. The problem becomes much bigger (even for Yale Bulldogs) when you remember that this metric doesn’t account for other types of debt not reported to the school, like second mortgages or borrowing against retirement funds.

Even taken at face value, the 72 percent statistic ignores the fact that huge numbers of Amherst students come from extremely wealthy backgrounds. Over 35 percent of students on campus didn’t even apply for financial aid last year. Let’s call this the Canada Goose demographic. If you assume that the vast majority of those in the Canada Goose demographic are at no risk of accumulating debt while in college, then Amherst’s numbers become far less impressive.

Of course, perhaps we shouldn’t expect so much from Amherst. Maybe the college has decided that a significant quantity of student debt is acceptable and inevitable. After all, Dean of Financial Aid Gail Holt wrote that “we’re exceptionally generous… [but] that doesn’t mean that we won’t ask you to make sacrifices.” But that isn’t consistent with the rest of Amherst’s messaging.

As we’ve already pointed out, Amherst’s website is rife with phrases that imply that no student needs to graduate with debt. Based on these statements, we might expect that Amherst students rarely take on devastating student loans, but that isn’t the case. However you take it, Amherst is either misrepresenting the effectiveness of its financial aid or failing to achieve its stated goals.

Before we close this week’s summary of the problems with Amherst’s financial aid, we want you to keep one thing in mind. Although student debt is a huge problem for Amherst’s students and their parents, the sums involved are relatively small for Amherst College itself. In 2019, Amherst students graduated with a grand total of $2.8 million in debt. It seems like a lot, but Amherst’s 2018 budget surplus — the leftover crumbs of its $200 million operating budget — was over $3.5 million. And that isn’t even mentioning the $2.4 billion endowment. We aren’t proposing that Amherst simply pay down all of its graduates’ student loans when they leave, but it could without batting an eye.

Hopefully, this piece has given you a taste of the problems in Amherst’s financial aid system. Next week, we’ll propose some possible solutions in the second half of this two-part series.

Unless otherwise cited, our data comes from each institution’s Common Data Set (CDS) for the relevant years. Amherst College’s are publicly available.

What’s your financial aid story? We encourage readers to comment below about their own experience, be it good or bad.

Comments ()