The World, Seen: On Beauty and Snow

Whose woods these are I think I know.

His house is in the village though;

He will not see me stopping here

To watch his woods fill up with snow.

My little horse must think it queer

To stop without a farmhouse near

Between the woods and frozen lake

The darkest evening of the year.

He gives his harness bells a shake

To ask if there is some mistake.

The only other sound’s the sweep

Of easy wind and downy flake.

The woods are lovely, dark and deep.

But I have promises to keep,

And miles to go before I sleep,

And miles to go before I sleep.

The image is that of a haze, with pinpricks of white obscuring the sylvan tapestry. In “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening,” Robert Frost shows his readers a man interrupted by the loveliness of his snowy surroundings, taking a moment of contemplation before his journey continues. There is no mention of coldness or wetness or eeriness, none of the “clammy and intensely cold mist…dense enough to shut out everything from the light” with which Dickens begins “A Tale of Two Cities.” Here, the precipitation-filled air charms the ambiance that arrests the driver, though not his horse, for a momentary pause.

Snow can inspire a surprising diversity of reactions. Lightly falling snow, as it flutters lazily to the ground, yields beautiful scenery. Heavily falling snow, on the other hand, often evokes fright and watching a blizzard from the comfort of a fireplace-warmed room is above all an experience of the sublime. Snow in trees can be stunning but treacherous, while snow blanketing the ground symbolizes the frigid air and early nights of winter. On asphalt, snow quickly turns to a repugnant slush, matching the consistency of watery swamp muck.

One popular contemporary explanation for natural beauty, Allen Carlson’s “environmental model”, explains that people find beauty in nature by paying attention to all of the details that make up peoples’ natural environments. People find beauty in the “blooming, buzzing confusion” of the world in identifying the living creatures that produce those sounds and sights. Taking pleasure in nature, then, “requires unobtrusive background to be experienced as obtrusive foreground;” as we bestow our attention on nature, we behold her beauty. But consider the snow falling in Frost’s poem, the whirling snowflakes falling to and covering the forest floor. If the beauty of nature results from nature’s details, then how could snow do anything but conceal natural beauty from the viewer’s eyes? How can snow, which blurs and obscures the natural world, lend itself to natural beauty?

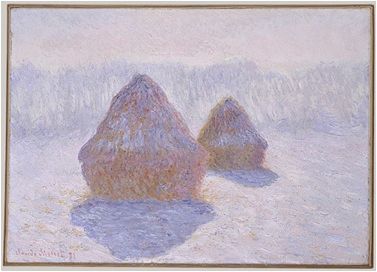

Though they offered no verbal answer, the French Impressionist painters of the late 19th century provide striking evidence of the beauty of obscurity. Replacing the perfect clarity of the salons with vibrant ill-defined color and form, Impressionists like Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir created works of art that exalt man’s indeterminate impressions of the natural world. Monet’s “Haystacks,” one of a series of haystack paintings from different seasons and times of day, emphasizes this indeterminacy by allowing snow to completely obscure the landscape surrounding his titular subjects. In this painting, it is not just the snow, but the scene as a whole, that we would call beautiful; it is the obscurity itself, and not that which obscures, that we value.

You are standing atop Memorial Hill, wearing a thick coat, staring out over a great snowfall. The snow blends in with the already-whitened landscape, as if a static television screen blocked your vision of the Holyoke Range in the distance. The scene captures your attention as it would capture the attention of any passerby, requiring its contemplators to squint, to stare, to try to make out the faraway mountains through the white-filled air. Even if you catch sight of a mountaintop here, a leafless tree there, it is not the identification of those objects that constitutes the overwhelming power of the experience; it is not the mountain or the tree that you would call beautiful. The experience is of no particular object, but includes everything, from the dry, crisp air to the snow-obscured peaks. There is no beautiful object. There is only beautiful experience.

This is the last issue of The Amherst Student published in the year 2012, and it is time to look ahead to the Amherst winter to come. Soon, days will arrive in which pulling up a window shade will bring the same vision that greeted Frost’s traveler, with swirling snow masking and enhancing the greens and browns that color Amherst’s campus in the winter. Like the traveler, then, we will have the opportunity to linger, for only a moment, and revel in nature’s unintelligibility, in color and shape and movement without meaning, all of which together demand our attention, calling us to look and to wonder. A moment, a pause, and then the necessary return to Amherst College, an institution that requires definition and clarity at all times from its students. For we are young, and we have miles to go before we sleep.

Previous articles from this column: On Beauty and Women, On Beauty and Advertising, On Beauty and Bedrooms, On Beauty and Big Bird

Comments ()