Writers Discuss Craft and Identity at Seventh Annual LitFest

The college hosted several award-winning novelists and writers, including Natalie Diaz and Viet Thanh Nguyen, at the Seventh Annual LitFest. They discussed themes of identity, language, and craft in their presentations.

LitFest, Amherst’s annual literary festival, returned for its seventh year on Feb. 25-27. This year, in its ongoing mission to “illuminate great writing,” the festival’s events tackled struggles of identity, the pursuit of accessing emotions, and the constraints of our preconceived notions of “writing.” Among those featured over the weekend were 2021 National Book Award nominees Katie Kitamura and Elizabeth McCracken, as well as Pulitzer Prize winners Natalie Diaz and Viet Thanh Nguyen, all of whom headlined events over the course of the weekend.

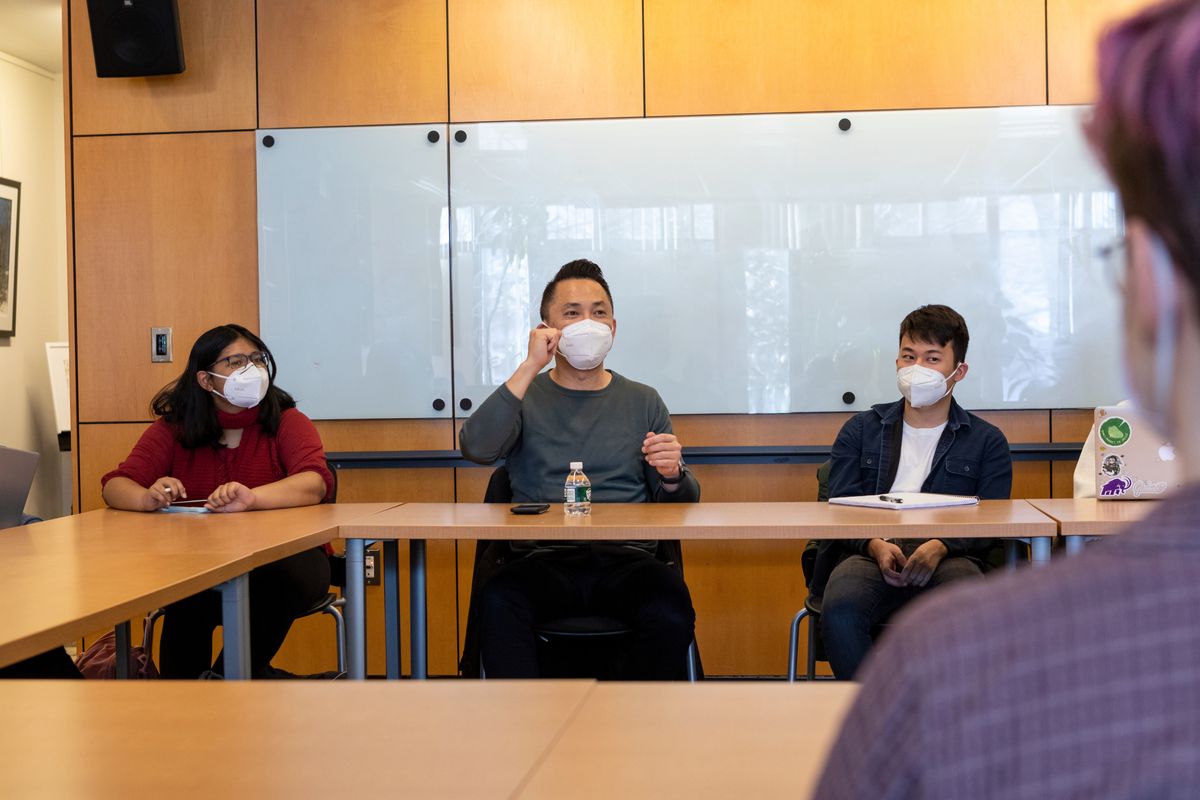

This year, students also had the opportunity to meet with authors in more intimate Craft Talks, a variation on the writing workshops or master classes that have been offered in the past. Kitamura, McCracken, Diaz, and Nguyen each offered hour-long sessions, during which they fielded questions from a small group of students on their writing processes, inspirations, challenges, and more. Other events included a Spoken Word Slam for Amherst students on Thursday night and several expert-driven sessions on Sunday, which focused on hot-button issues like voting, democracy, and immigration.

Organizers took a hybrid approach to LitFest this year, marking a partial return to normalcy after last year’s entirely virtual event due to the pandemic. Several sessions were offered both in-person and through livestreams, a decision that served multiple purposes: accommodating non-Amherst audiences tuning in for the public events; protecting against the recent Covid surge that the school has faced; and, on Friday, accommodating the college’s snow-induced closure.

LitFest officially kicked off on Friday night with a virtual conversation with Kitamura and McCracken. In her opening remarks, President Biddy Martin spoke about the event’s importance to her throughout her presidency, which will end in June. “Amherst nurtures writers and literary culture, and I hope it will always be so,” she said, praising the festival as “one of her favorites.”

The conversation was moderated by Kirun Kapur, lecturer in English and director of the Creative Writing Program, and focused on the themes of Kitamura’s novel “Intimacies” and McCracken’s short story collection “The Souvenir Museum,” which were both longlisted for a National Book Award this year.

On Saturday morning, poet Natalie Diaz joined the festival virtually from her home on the Fort Mojave reservation to discuss her recent poetry collection, “Postcolonial Love Poem,” in a session hosted by Professor of English Alicia Christoff. Diaz began the session with a reading from her poem “I, Minotaur,” in which she explored “ideas of ‘American goodness’” that seem “impossible for some of us to achieve.”

Angelina Suarez ’25 attended the session and described it as “a good conversation” that “felt very rushed.” Suarez is studying “Postcolonial Love Poem” in two of her classes, and was required to attend the session for one of them. She wished the event had gone on longer and allowed more room for student questions, but voiced gratitude that there was time for her own question about the mentions of war in Diaz’s poems and how they translate to her real life (to which Diaz acknowledged the complexity of the question, and mentioned that war can emerge in many forms, including the language that has been used to perpetuate difference and hierarchy between racial groups).

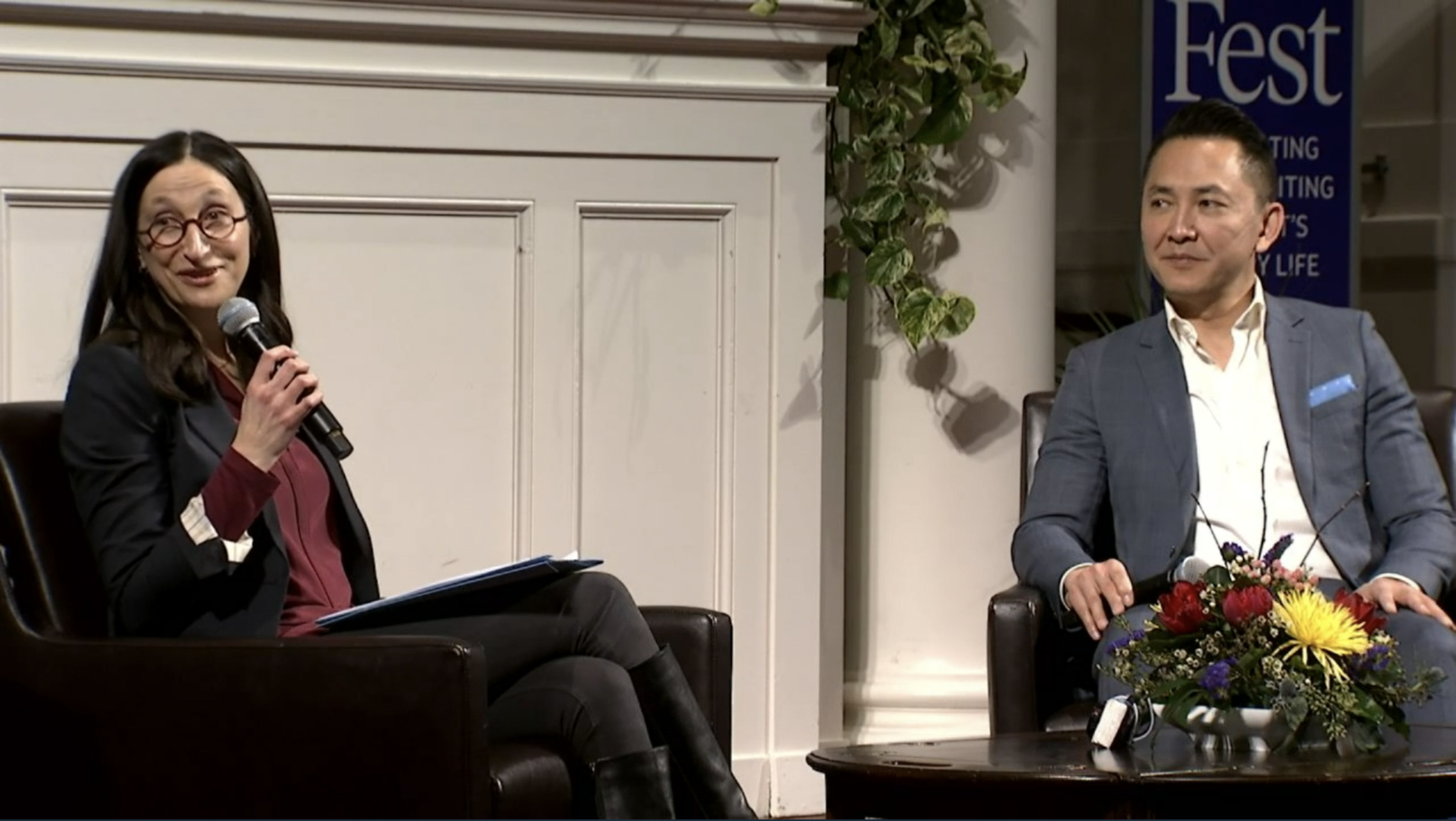

Saturday’s keynote speaker was Nguyen, who spoke with Editor-in-Chief of The Common Jennifer Acker in an event titled “The Art of Belonging: A Conversation About Race, Migration and Fiction Writing.” Nguyen discussed several of his books, beginning with his first, “The Refugees,” a short story collection that took him 17 years to write, and moving to “The Sympathizer” and “The Committed,” his more recent works and the first two installments in an ongoing trilogy.

Most notably, Nguyen recounted the challenges of writing boths works, and the subsequent lessons he was able to learn. With “The Refugees,” he spoke about his extended writing process — one that came with “depression, insomnia … and doubts” — and the difficulty he had with finding each protagonist’s voice. By contrast, he described his close relationship to the main character of “The Sympathizer,” who was a sort of “alter ego [of himself] — …in terms of beliefs and values.” As the character developed, his flaws became clear — and with them, Nguyen’s own.

“In writing this book, I had to confront my own misogyny,” he said. Writing “The Sympathizer,” and later hearing critiques of it, forced him to learn and grow.

Nguyen didn’t recall these criticisms with resentment — instead, he praised them and those that are willing to offer them, even if he sometimes disagrees.

In an interview with The Student, Nguyen echoed the value of impactful college experiences — those like LitFest, but also the experiences that come from interacting with professors. He said he hopes what students get out of both his words, and their Amherst education in general, is a “passionate commitment to doing something that matters. One of the important things from my college experience … was that I [became] super passionate about literature, politics, activism, social change, and how they’re all related. That has never left me.”

Sarah Wu ’25 read “The Refugees” as part of her fiction writing class this semester, and attended several of Nguyen’s events. “I think for me, the biggest part [of Nguyen’s talks] was his process. I always ask, ‘How do I prevent self-stereotyping?’ I always have this fear of … misrepresentation. He really gave me perspective, in terms of being able to write for myself. It was really mind-boggling.”

Wu is an intern for The Common and a writer herself. She read her own work, a short story about cultural identity, at a LitFest event on Saturday afternoon. After hearing Nguyen speak, she has “many thoughts” on how she could deepen the narrative, which she said she’ll carry to future projects.

Though each LitFest author comes from a different background and writes on different topics, certain themes continued to arise as the writers shared the inspirations and thought processes behind their work.

One of these echoed topics was the notion of identity: all of the authors touched upon how their own lives have shaped their work. Kitamura offered an explanation as to why identity and fiction are so interconnected: “Whether you like it or not, you are all over your work. There is no point in trying to move away from yourself.”

“Identity isn’t a stable thing; it’s shifting all the time. There are gaps that open up — how you navigate that is something I try to explore within my work,” she added.

McCracken reflected on how changing perceptions of her own identity impacted her work after the death of both of her parents. “Suddenly I am the upper generation … there was something quite profound to me,” musing that the consequences of this realization sometimes affected her writing in “inopportune” ways.

Nguyen discussed his own experience navigating identity and labels. “Often, I’m asked, ‘Are you a writer or an Asian American writer?’ — binaries that are only placed on writers of color. You need to refuse those terms,” he said in his craft talk. “There is no world in which being a representative of an entire community is good for a writer.”

Suarez thinks conversations about identity are crucial on a campus like Amherst’s — particularly for students like her, who haven’t had past exposure to the topic. “Where I come from, we don’t really talk about our identity. I'm from Texas, we’re a very conservative state.” she said. When entering these discussions, she described feeling “vulnerable and inexperienced. I’m not sure how to navigate it, so I just try to absorb as much information as possible and figure it out.”

Another common theme of the festival was the limitations of language. Though Nguyen and Diaz spoke separately, both of their sessions worked to create a dialogue about their experiences with English’s shortcomings.

Ironically, Nguyen began his craft talk by rejecting the term ‘craft’ — “Ideas make a difference; they have an impact,” he said, “Craft for the sake of craft is technical, [it’s] pointless.” Nguyen stressed the importance of careful thought when writing. “Even basic choices of character are not just craft — they’re politics [and] show implicit prejudices,” he said.

Diaz, too, discussed her criticisms of language. Her writing is influenced by the three languages she speaks — English, Spanish, and Mojave — and she believes that English needs to be more fluid and expansive. “The English language is always in a state of emergency. Our understanding of English needs to be capacious,” she said. “Languages are shaped in the lands they’re spoken in; they are knowledge systems, [and] knowledge is so dangerous because it stops.” As such, she believes languages must stretch to encompass the knowledge of all of its peoples: “Indigenous languages are a crucial part of the American lexicon.”

Nguyen also called for a widening of our understanding of English writing. For him, this means tackling the concept of translation — not only of words, but also of culture and customs. “Art from artists of color is marked by implicit translation,” he says. “We are expected to write to the majority audience because they have the power … To write to Vietnamese audiences is a revolutionary act.” Ignoring the “burden” of translation, as he did with “The Sympathizer,” has made his work “free.”

Even as they work to shift preconceptions in their fields, neither author believes their work is a replacement for institutional societal change. Diaz, who often hears about the ‘empathy’ her work inspires, thinks the term is empty and problematic. “I don’t believe [empathy] has ever done anything for my people. It doesn’t often lead to action. I feel similarly about poetry.”

Nguyen said the same. “I don’t believe in healing through literature. Grieving and mourning, yes, but it can’t heal.” Even so, he urged readers not to lose sight of the bigger picture. “Healing as a country is not about individual grief. The collective, historical contexts aren’t going away.”

Instead, the authors spoke to the importance of translating their work to tangible efforts. “If [poetry] can bring us to a practice of tending to each other, that means something,” said Diaz. And from Nguyen: “Literature can’t change anything. Action can.”

These words hold particular value at an event dedicated to the power of the written word. As LitFest comes to a close, the themes remain. “I just keep going back to process everything,” said Wu. “I want to hear everything again.”

Comments ()