Remembering Black History Month and Centering Black Women at Amherst

Staff Writer Sarria Joe ’27 continues to discuss this year’s diminished Black History Month celebrations and what the annual observance means to Black students at the college, particularly Black women.

Amherst’s lack of institutional acknowledgment and celebration during Black History Month this year was deeply dismaying. As I peered through the Black Students’ Union (BSU) archives and witnessed the robust and collaborative planning process surrounding Black History Month, I was confounded by the administration’s current inadequacies. Additionally, my conversations with Senior Associate Dean of Students Charri Boykin-East illuminated the once-active efforts between institutional departments, committees, and the town community and their acute involvement in the planning and execution of events centered around honoring Black culture, our contributions, and Black students. Once again, this raised questions on how the past compares to the present and how looking into the past can help improve our future.

What Black History Month Looked Like This Year

The administration made some respectable efforts this year — the college expanded the Ancestral Bridges exhibit, hosted an athletics Black History Month alumni panel, and invited Natasha Trethewey, a distinguished poet and writer, for a conversation with President Michael Elliott. However, as I reported in a previous article, institutional acknowledgment and publicizing of Black History Month events remained severely lackluster.

Dean of Students Angie Tissi-Gassoway attributed this year’s lack of robust programming to leadership transition. She explained that our new chief equity and inclusion officer, Sheree Ohen, just arrived in the fall semester and is “still learning our histories, how we have celebrated Black History Month and other cultural heritage months on campus in the past, and how she wants to shape the role [the Office of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (ODEI)] has with [Black History Month] and other celebratory months.”

Dean Tissi-Gassoway added, “The Office of Identity and Cultural Resources (OICR) has also gone through a lot of transition as well as Student Affairs ... our Multicultural Resource Center (MRC) director is on leave ... so that has obviously had an impact. So it’s, in some ways, a capacity issue."

Similar to what I witnessed within the BSU archives, the weight of planning and executing events specifically to commemorate Black History Month falls on the shoulders of affinity groups and identity resource centers. This year, events like the Black Arts Matters Festival were organized by BSU, the African & Caribbean Students’ Union (ACSU), and the MRC, with the visual showcase held in collaboration with the Mead Art Museum.

Moreover, the BSU, in collaboration with the ACSU and the Peer Advocates for Sexual Respect, organized a “Black is Love” event in the MRC to discuss Black love in film, media, and books. This discussion was facilitated by Associate Professor of American Studies Aneeka Henderson, who prompted students to reflect on their encounters with Black love in certain mediums and how that has shaped their romantic and platonic experiences. Among the events to close Black History Month was a dinner hosted in collaboration with the ACSU and La Causa.

“Regarding [the] BSU, [the] ACSU, and the MRC, it’s not their job to have to inform everyone on how the school should conduct its business,” said Eleni Hailemicheal ’27. She explained that “Black History Month is about liberation and celebrating liberation. Putting the pressure of organizing on affinity groups [that] are made up entirely of students defeats the purpose when they are being overburdened.”

The lack of visibility for Black History Month this year was especially confounding because it was not like this a few years ago.

In February of 2023, Amherst formed the Amherst Uprising Alumni Panel, which the Black History Month Planning Committee organized in joint efforts with the MRC, ODEI, and the Cultural Heritage Committee. In the panel discussion, alumni from the 2015 uprising reflected on their sit-in in Frost Library and how that sparked a movement demanding the college to dismantle their “institutional legacy of oppression.”

A few days later, the MRC, in collaboration with ODEI, invited Nekima Levy, an acclaimed civil rights attorney and racial justice activist, to be the keynote speaker of the MLK Symposium. Levy, in her keynote address titled “From the Classroom to the Streets: The Struggle for Justice Continues,” discussed the importance of bringing her law students, most of whom were very privileged outside of the classroom, to “make a difference ... have them organize events and be uncomfortable.”

Centering Black Women

As I looked through the BSU archives, I found it notable how they intensely emphasized the protection, representation, and support of Black women on campus. Even in later years, members of the Amherst community have dedicated themselves to representing and uplifting Black women and their work at the college.

Boykin-East said, “Janice Denton, a former staff member of Frost Library for many years, along with a number of her other important contributions also every year, created beautiful displays in the library to celebrate and honor Black History Month.”

She continued, “These displays not only at times depicted important historical events at the college and within the Amherst Community ... the displays also included historical figures, artifacts, photographs, and other references that helped to tell the incredible stories of Black experiences in America.”

Around 1999, the late Mavis Christine Campbell, emerita Professor of History, published a book, “Black Women of Amherst College.” Two decades later, Black Amherst alumni created a podcast series inspired by Professor Campbell’s book, which focused on discussing “activism and academics, progression and regression.” The podcast features faculty members and alumni, including Sonia Sanchez, the Emily C. Jordan Folger Professor of Black Studies and English Rhonda Cobham-Sander, and former Associate Dean of Students Onawumi Jean Moss, detailing their stories and experiences as Black women at Amherst who have played a role in the development of students as well as the institution.

Associate Professor of American Studies Aneeka Henderson described a book club she created for Black women on campus: “We read novels by Black female authors, discussed them over dinner, and then we would go and see those authors talk about their work ... That was just a wonderful space to discuss literature, culture, and history without the pressure of feeling like you’re being assessed or graded ... We created something really special through our book club discussions. It helped build community and serves as a reminder that we need to have more community-building programs on campus that center on Black female students. It is imperative.”

“We also went to New York City to see a play. And that was just a wonderful experience as well. Also, I took some time to teach students how to jump Double Dutch ... those kinds of things are important ways of fostering a sense of community and solidarity as well as celebrating Black women’s creativity, history, and art,” said Professor Henderson.

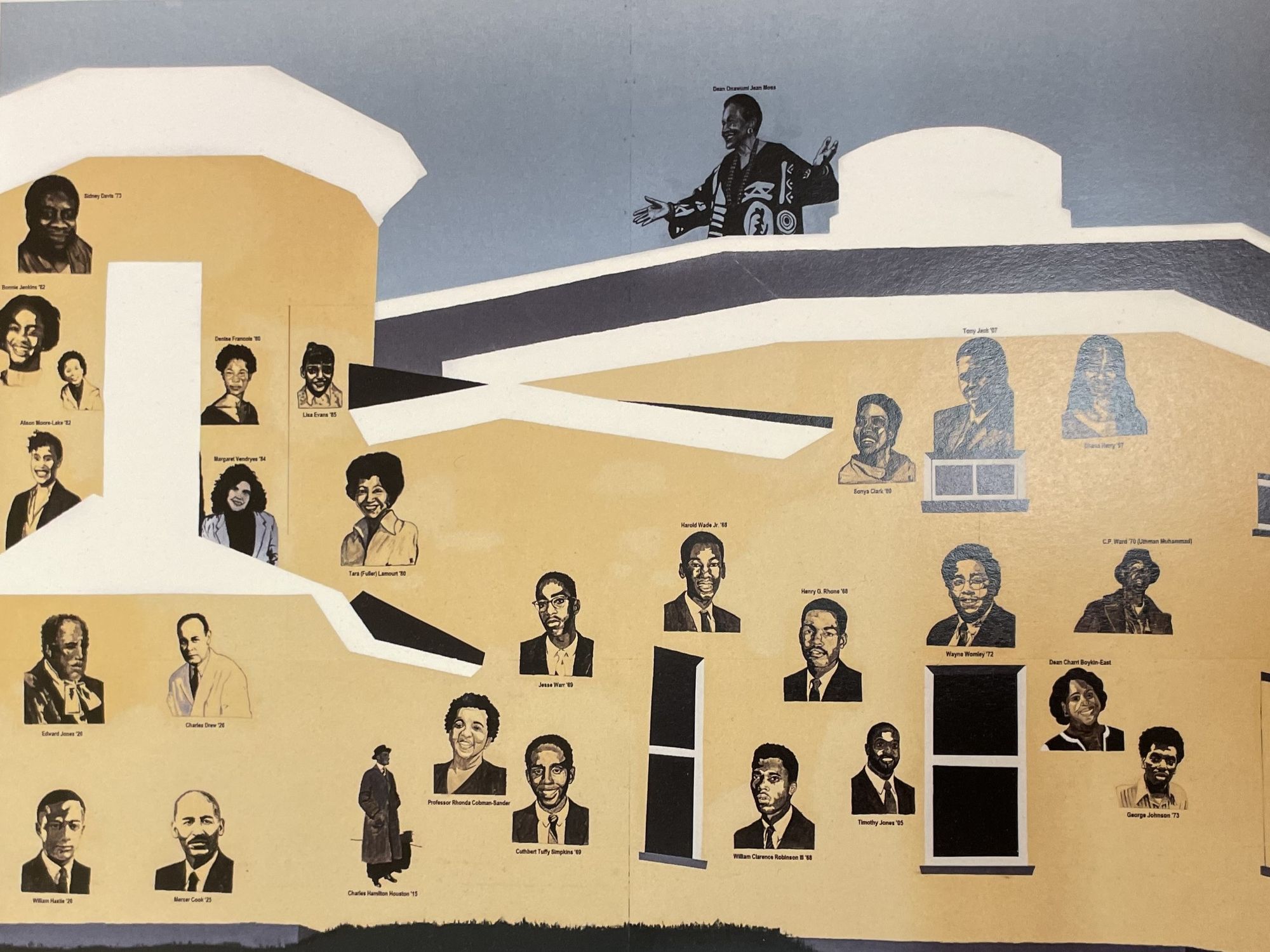

Among other contributions to celebrate Black women on campus was the addition of faces on an old mural in the Octagon painted by Kevin Soltau ’01, which included Professor Rhonda Cobham-Sander and Dean Charri Boykin-East. This visual showcase for Black alumni is deeply important and has inspired current Black students, allowing them to see themselves represented through past and present faculty and alumni.

Arianna Dempsey ’27 said we sometimes underscore the impact of the work and developments by Black people, especially Black women, in our daily lives: “We don’t ever realize how much work was put into a certain development or the impact of the fact that it was a Black person, let alone a Black woman, who has advanced our world.”

Although these projects are commendable and inspiring, there is still much more that needs to be done by the administration to represent and support Black female students, faculty, and staff on campus, especially during Black History Month and Women’s History Month. Women’s History Month serves as the perfect opportunity to continue highlighting the stories of Black women, which are typically underrepresented even during Black History Month. Yet we have witnessed little to no acknowledgment and programming by the administration on uplifting Black women or bringing awareness to issues on campus and in the world currently affecting them.

The brunt of organizing should not fall on the shoulders of Black female students, faculty, and staff, considering they are already overwhelmed with the stress of navigating their personal lives, academics, and the social climate at a predominately white institution. For an administration that strives for gender inclusivity and diversity, the institution needs to implement programming yearly, especially around these celebratory months, to ensure that the lives and contributions of Black women are not continually undermined.

What Black History Month Means to Students, Faculty, and Staff

To adequately honor Black History Month at Amherst, we need to remind ourselves why it exists in the first place and the importance of maintaining this tradition.

Most of the Black students I spoke to reaffirmed the purpose of Black History Month as a time of celebration, appreciation, and relearning of our history and culture. In addition, they emphasized the importance of acknowledgment as well as action from the administration.

“[Black History Month is a] time to reconnect with your culture and also to relearn history. Honor it, educate people, and educate yourself even more,” said Maigan Lafontant ’27. As a Haitian-American, she emphasized that it’s important to raise awareness of underrepresented narratives where Black people were the prime organizers in the revolt for their liberation.

Association of Amherst Students (AAS) Senator Noah Turbes ’27 said that it’s especially important to acknowledge and celebrate this month because “A lot of people are not aware that Black history is American history ... It’s important that we bring [Black history] to the forefront and remind people who built this country, as well as the culture and the voices that continually shape the American dialogue.”

Black Amherst professors said they use their classrooms to celebrate through the centering of Black people and our contributions.

Assistant Professor of English Frank Roberts explained, “We are witnessing an unprecedented attack on Black cultural institutions and Black cultural traditions. There’s an old proverb that our existence is resistance. And when we say our existence is resistance, we don’t just mean our bodies; we also mean our traditions, including Black History Month.”

Faculty evidently recognize the importance of uplifting the community during this time.

Chief ODEI Officer Sheree Ohen said, “Black History should always be celebrated, but I think honoring it, particularly in February, highlights the unique achievements that our people have made and the erasure of many of the contributions of people in the Black diaspora. Black History Month allows us to make visible the lives of people and the humanity in Black people.

Black Liberation & Our Commitment to Activism at Amherst

As we have learned and discussed repeatedly at Amherst, the history of Black Americans and Africans is full of our resistance and struggle for liberation. An old statement of purpose by the Afro-American Society explained how the systematic denial of Black people’s cultural heritage and humanity “has been perpetuated through the College’s insensitive policies towards institutionalized support for the Afro-American experience.” Thus, their mission as a group was to primarily support Black students’ well-being on campus as well as enhance the college’s relationship with aspects of the Black experience. Among the many ways they sought to accomplish these goals was by speaking up and advocating for pertinent issues of and relating to Black liberation.

A prime example of this was in 1985 when BSU discussed the formation of a committee to address apartheid in South Africa and even drafted a letter to the Board of Trustees of Amherst College asking, “How can Amherst College, an educational institution that heralds itself as a propon[e]nt of liberalism and diversity, continue to support the blatantly racist system of apartheid in South Africa?” Some students at Amherst College today are asking the administration the same question regarding the genocide in Palestine.

Moreover, BSU strongly rejected “the policy of ‘constructive engagement’ being pursued by the United States government and this college.” Likewise, some students, as well as faculty today, have expressed a similar sentiment, citing the administration’s silence on denouncing Israel’s culpability in the genocide of Palestinians as well as silence on the genocides in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Sudan, and Tigray. The imbalance of wealth, military resources, and political allies that Israel has over Palestine demonstrated from the beginning that this was a purposefully violent orchestration of genocide, not war. The administration needs to understand that it can not educate on the values of Black liberation without the fundamental conviction that the liberation of one must include the liberation of all. Historically, Black scholars and activists have stood beside Palestinians and their fight for freedom and sovereignty. In addition, the genocides in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Sudan, and Tigray require more attention from the institution as they are receiving less coverage in the media due to anti-blackness and colorism. This is not the first time in history that the persecution and suffering of Black bodies have been ignored or suppressed.

Considering Amherst’s pledge to fight systemic racism and other social justice issues, we are at a pivotal moment in time when the institution needs to take a stand against colonialism and support students who are protesting for an immediate and permanent ceasefire. It’s vital that programming during Black History Month and Women’s History Month illuminate the intersectional reality of suffering, assault, and oppression that Black and Brown communities face in America and the world.

Some students also stressed the immense responsibility of Amherst to acknowledge these prominent social justice issues.

George Daniel Dixon ’27 said, “Amherst can start speaking up because Amherst has a lot of political power, and we can make a difference on these issues ... if Amherst can be brave enough and take a first step to contest these ideas, other colleges will start to take that same step.”

Amherst’s ideology of neutrality has created a fear of speaking up and standing alone or among the few who seek to call mass atrocities for what they are and condemn oppressors instead of coddling their feelings. The administration, particularly the Board of Trustees, needs to ask within itself: How can we continually extend sensitivity and empathy to people who have shown they lack remorse and the decency to extend those qualities to others?

As we reflect on our commitment to activism at Amherst, we should keep in mind the words of Sonia Sanchez, a renowned poet and second chair of the Black Studies Department.

Following the Dr. Martin Luther King Legacy Symposium in 2018, Director of Digital Communications Roberta Diehl wrote, “Over the next hour, Sanchez implored us to think about how we would answer a question our children might one day ask: ‘What did you do when the poor suffered, and tenderness and life burnt out in them?’ Our answer, according to Sanchez, must be: we resisted.”

How Do We Move Forward?

“Black History is American history” has become commonplace in conversations about commemorating Black History Month. While this sentiment is true, it has been used to divert attention and conversation from recognizing and celebrating the contributions and culture of Black people during our annual observance. It’s deeply important for the administration and students to remember that this time was carved apart for a particular purpose. Black people’s nuanced narratives, critical contributions, and captivating culture are continually suppressed and revised in readings about American history. The month of February sets apart a time to remember how far we’ve come and how much further we need to go.

As the cliche goes, the past informs the present. Dean Charri-Boykin East said, “Every year, we have a new and vibrant community. I welcome the opportunity to work with students, faculty, and staff to continue to find ways to share our rich history both here at Amherst and our history beyond Amherst.”

To reckon with the lack of institutional acknowledgment and programming this year, faculty and staff stressed collaboration across departments and communication with students and faculty to gauge their needs.

Chief ODEI Officer Sheree Ohen explained that she’s been conversing with Jennifer Chuks, who is jointly appointed with the ODEI and Athletics, and Crystal Norwood, who oversees Student Affairs and the OICR. “We’ve all talked about how we want to continue thinking about how to make [Black History Month] more robust in [upcoming] months. It’s also really exciting to see that all of us are black women ... It’s really important to us, but we also believe in executing thoughtful and sustainable programming or initiatives instead of throwing things together,” said Officer Ohen.

She said, “One of the opportunities that we have talked about with Crystal [Norwood] and my Associate Chief, Traniece Bruce, is convening a committee that starts meeting early in the term so that by the time February comes around, we already have a plan that includes consultation with students throughout the year.”

Professor Roberts explained that students’ discontent at the absence of programming and conversation during Black History Month is unsurprising and stressed the importance of sparking these conversations ourselves. He said, “What we need is a community of visionaries and dreamers who are going to do what Black students have always done at Amherst College, which is make Amherst a better place. And so, to me, this moment is really about how can students continue that tradition?”

Some students believe that since Amherst implements a myriad of policies and programs to recruit Black students; thus, it is the administration’s responsibility to spark these conversations.

Erin Nwachukwu ’25 said, “If you want me in this space, I would hope that you would then make considerations for what I might need in this space ... or ask yourself what might help me feel welcomed in the space so that you can have those things in place for me when I arrive compared to me having to show up and then tell you this is what I mean.”

“One thing I can say is feeling seen and feeling supported, also seeing people who look like me in positions of power are one of the first steps the college can implement in celebrating Black students,” said Siani Simone Ammons ’27.

Ultimately, as an institution that prides itself on liberal arts values and ensuring diversity, the administration needs to do more to show its diverse student body that they are recognized and supported. Our intellectual discussions in classrooms, talks, and lectures surrounding pedagogies, concepts, and ideas of oppression and inequality should not be akin to a game of tennis. A mere back-and-forth centered on hitting academic buzzwords and serving jargonistic attitudes limits our ability to enact meaningful change. If Amherst is truly committed to “enlighten[ing] the lands” as we preach, the institution must commit to persistent programming. It is crucial to Amherst’s mission to fully represent, support, and uplift Black students, particularly Black female students, faculty, and staff, as well as center issues pertaining to their liberation and joy on campus and in the world.

This article is the final piece in a series investigating what Black History Month looks like at Amherst and the perspective of students, faculty, and staff on the significance of this annual observance and what the future should look like.

Comments ()