Balmain Festival 2021: Freedom and the Future of Fashion

Contributing Writer Noor Rahman ’25 covers the recent Balmain Festival, highlighting the significance of the festival’s homage to its creative director, Olivier Rousteing, the only black head of a major fashion house.

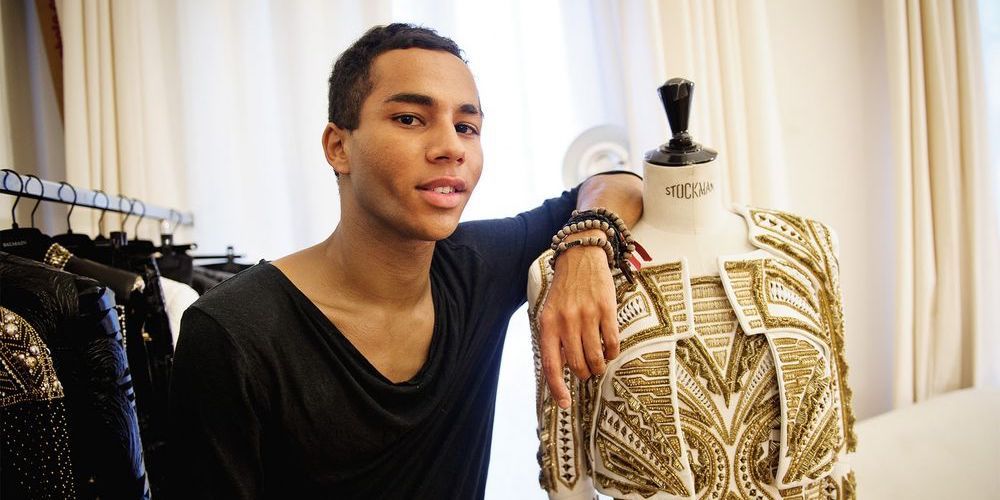

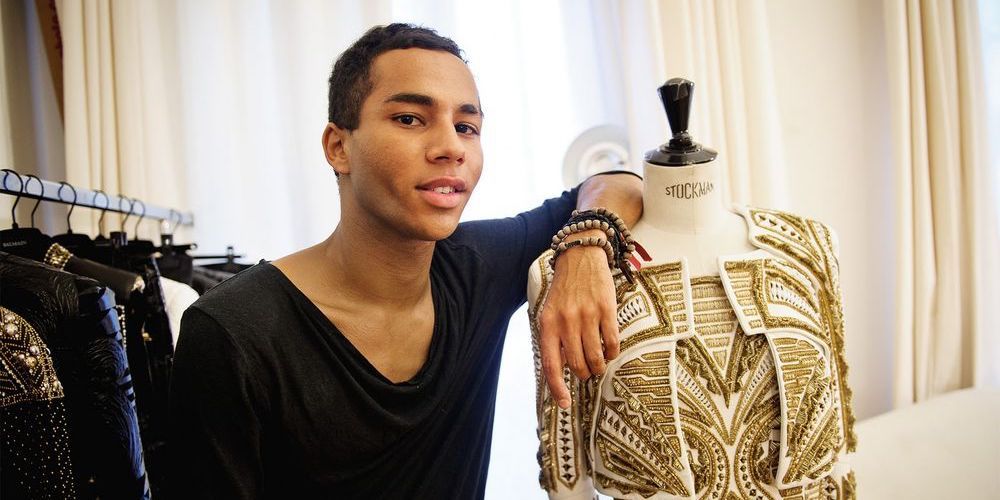

Last week from Sept. 28 to 29, luxury fashion house Balmain held its annual Balmain Festival at La Seine Musicale, a music hall on the Seine river in Paris. The festival included A-list celebrities, a pop-up Balmain village open to the public, live performers, a live fashion show and notably, a message from Beyoncé. For Balmain and the fashion industry, it was a triumphant celebration of the 10 years Olivier Rousteing has served as the brand’s creative designer, one of the first Black heads of a major fashion house. The festival was an homage to a man whose mission has been diversity and democratizing fashion since before anyone was paying attention — before it was a PR tool, before “diversity” was a buzzword, before it was cool.

The festival featured areas open to the public, including access to the Balmain pop-up village. The village included food trucks, stores with Balmain merchandise and even blow-dry bars. All proceeds from the festival were directed to (RED), an organization dedicated to fighting AIDS. The show inside the music hall was live-streamed outside on giant screens for viewers to enjoy. Total attendance, both inside and outside the music hall, was estimated at 6000.

Inside the music hall, live performances included Doja Cat, Franz Ferdinand and Jesse Jo Stark. Beyoncé, although not physically present, was featured in the form of a prerecorded video homage to Olivier Rousteing. Her message was personal and heartfelt, touching upon Rousteing’s dedication to opening up the runway to all, instead of just for the elite: “Once you made it through that door, you did not shut it behind you. For 10 years, you have been determined to keep pushing that door open wider, making sure that others can also have opportunities for reaching their dreams……”

For Rousteing, the festival was all about freedom, which may sound trite, but has implications both for Balmain and Rousteing personally. Rousteing became creative director of Balmain in 2011, succeeding Christophe Decarnin, whose modern, rock-and-roll take on couture was beloved by the industry and brought Balmain back from a long period of relative insignificance.

Rousteing, upon taking up Decarnin’s position, was quickly written off as over-the-top and gaudy. His clothes were partly traditional couture but were heavily influenced by street style fashion, which had yet to become a major motif on the runway. From the outset, he utilized social media as a means of communication with the world at large rather than exclusively marketing to the elite. He was one of the first designers to launch an Instagram page, and he quickly secured the Kardashians as allies. And for a time, he was the only Black man at the helm of a major fashion brand. Rousteing has slowly but surely broken out of the box he was initially placed in at Balmain, helping it to become one of the foremost designer brands in the industry. Most admirably, he did so without compromising the maximalism of his designs and his commitment to the accessibility of fashion.

Over the last decade, Rousteing’s public image has changed drastically from a blingy Instagram page rife with impeccably posed pictures of himself to a genuine story of someone unsure of his own identity. For a long time, the public had no access to Rousteing beyond his carefully curated image. That changed in 2019 when “Wonder Boy,” an unexpectedly raw and emotional documentary about his search for his birth parents premiered. Rousteing told the New York Times,“They think I am the designer who loves myself, because I post so many selfies. But I realized I had become a caricature of myself, and trapped myself; that the image was my protection, because it meant I did not let anyone into the truth of my world. I want to lose it; I want to be myself rather than the person I pretend to be.”

The festival, specifically the runway show, was filled with symbolism and references to the journey Rousteing has taken. It celebrated all the elements that have come to define Balmain today: 1980s revivalism in the form of neutral tones, gold embellishment, sequins and pearls, shoulder-padded jackets and bodycon dresses.

Keeping with his newly found tradition of openness and authenticity, Rousteing shared that he had been badly burned in an accident involving his fireplace last October, which served as inspiration for this show. The gauze with which he had become familiar through his recovery was a major motif. Many of the dresses resembled bandages coming undone, and material resembling gauze was featured abundantly.

In addition, all of the models wore stacked gold rings, similar to those Rousteing had worn to cover the scars on his hands. “It made me understand how important comfort is,” he told the New York Times. “And how clothing works to help you show what you can show, and hide what you need to hide, without anyone realizing what you are hiding.” The emphasis on comfort was reflected in the presence of baggy cargo pants and chunky, braided pieces.

The festival certainly accomplished its purpose in more ways than one. The event felt much more accessible to international viewers and those not directly in the fashion industry than the typical runway event. It also balanced the celebration of Balmain and Olivier Rousteing beautifully. The show signified perhaps a new beginning for Balmain, as Rousteing remarked “It’s a collection that talks about the freedom to be yourself, about having the confidence to move forward into a new world, both with the clothes and for myself. It’s been 10 years so I wouldn’t say I’m opening a new chapter. I’m opening a new book.”

Comments ()