“BlacKkKlansman” Promises Radicalism, But Fails to Deliver

For a brief moment in the final stretch, “BlacKkKlansman” sheds the infiltration shenanigans and the tired cop camaraderie. The audience sit down with the Colorado College Black Student Union to hear an older individual’s whispered account of horrifying crimes, who speaks of what he saw on a particularly hot day of 1916. They castrated Jesse Washington. Then they burned him alive. The students sob even without proof, but the old sufferer shows them anyway: how they cut him, how they killed him. The camera pushes in from his face to his hands, shuffling the colorless photographs one by one.

The effect is a movie of sorts, one picture following another. Eisenstein once described his theory of montage in cinema in this way: there was to be an image followed by another image. There would be only two images, but we would see three: a third, invisible image to shock, hurt, teach and empower. In a sense, this unassuming gesture captures 20th-century American race relations with Soviet film techniques; as the speaker slides from one photograph to another, we witness the red between the black and white.

Of course, Spike Lee’s filmmaker of interest is not Eisenstein, but D.W. Griffith, whose acclaimed opus “Birth of a Nation” is referenced on occasion as Ron Stallworth (Jon David Washington) drives Flip Zimmerman (Adam Driver). And the technique of interest is not montage but cross-cutting, a montage of event. “Birth of a Nation” infamously cut between stereotyped black men’s raids on innocent maidens and the charge of the white brigade to imply two possible third events: miscegenation or deliverance.

When that tension resolved as the latter, Griffith cuts between a marriage and voting suppression to imply a hopeful inevitability: the white race will rebound from the Civil War. Lee’s Klansmen, who are watching the film at the same time the witness is giving his testimony, probably do not understand its cinematic intricacy. But they nonetheless cheer as the “villains” are torn away to be castrated and burned.

This moment is the heart of “BlacKkKlansman,” and it is by far its most impressive scene. Lee homages Griffith by also crosscutting between scenes involving different races. The aging eyewitness also remembers the national popularity of “Birth of a Nation” and how the meekest citizen found entertainment in the torching of a black teenager. His hands, still shuffling and at times shaking, hold the images that must replace Griffith’s. And when we cut back to the Klan crew seeking to remake “Birth of a Nation,” “BlacKkKlansman” is a tremendously clever rebuttal that fights form with form. “Black Power,” one side chants. “White Power!” the other side responds. The war has begun, and the third event will be the triumph of either black or white.

In some corner of David Duke’s (Topher Grace) frothing gathering is Detective Stallworth, sending signs through his shades to Detective Zimmerman. That corner is where they belong. It is a massive letdown that the actual content of “BlacKkKlansman” does not consist of the formal infiltration of black image in white, but rather the far more mundane double-agent, buddy-cop businesses that went bankrupt in the time of Denzel Washington, John David’s father.

And with such little intrigue, Washington and Driver must split its impoverished portions. Driver, delivering every line as a grumble, has physical presence and nothing else. Ron suggests the operation because his encounter with Kwame Ture (Corey Hawkins) and his radical girlfriend Patrice Dumas (Laura Harrier) awakens a vague fire inside his heart.

Flip is a machine powered by another man’s heat: the struggle never becomes anything personal to him. From beginning to end, he is Ron’s proxy with a gift for improvisation. Once or twice, he brings up his Jewish identity and his unease at the precarious position of his people in the white community. Every other time, Flip busies himself concocting some funny and racist answer to a suspicious Klansman looking at his jeans, interrogating whether he had been “circumstanced.”

Ron is cut down by the opposite problem. Because he himself cannot roam amongst the Klansmen, Ron has little to no weight in the story. Over the phone, he speaks in an exaggerated white accent to David Duke, and the Grand Wizard is fooled by it, letting his racist intuition get in his way of identifying and discriminating against an actual black man, who fakes the white accent to get his way. For the audience, this may result in a chuckle or two.

In short, Ron as a vocal presence is a joke. When he is not on the phone, he spends time with Flip and Patrice. Interactions with his partner never progress beyond the operation, thus letting down even the most rudimentary expectations of the tired buddy-cop genre. Ron is markedly livelier with Patrice, mostly because she offers the few opportunities for Washington to inhabit a scene with another actor.

But it is here that “BlacKkKlansman” relinquishes the radical potential of its highest moment. He laughs, he orbits, he flirts and he spins. In the meanwhile, he challenges Patrice’s radicalism, and even as he conceals his identity as a cop (or to Patrice, a “pig”), he remains steadfast in his belief that the system can be changed from the inside. This is a bizarre step for Lee, one that lets down not only the best part of this film, but the best film of his career. Lee’s 1989 masterpiece, “Do the Right Thing,” portrayed a scorched landscape of racial animosity and misunderstanding with no clear idea about what the right thing was. But the wrong thing was clear enough: the police and their insensitivity, addiction to force and propensity for extrajudicial murders. Stallworth is a cop, but in “BlacKkKlansman,” Lee sides with him and his institution, and this picture composes a curious montage that seems to be missing an image between the old and the young.

That image may be the New York Police Department’s $200,000 grant to the director, made with the expressed purpose of “improving relationships between the police and the community” and the implied purpose of something, at best, related. At his best, Lee fights form with form; at his worst, he fights back with similar tactics. After the cross-cutting between black power and white power, Stallworth’s dealings with Patrice and Lee’s dealing with the police delivers a third image of compromise and disappointment.

That image is the general impression of the canonical filmmaker’s supposed return to form. The end of “BlacKkKlansman” tries to revive the excitement of its highlight, by situating the film in the broader montage of history. It cuts from the 1970s to the present day — to Trump and Charlottesville, the grain of the witness’ photographs replaced with the crisp colors of cable news. But this is too little, too late. The relationship between the film’s contents and Charlottesville is simple equivalence.

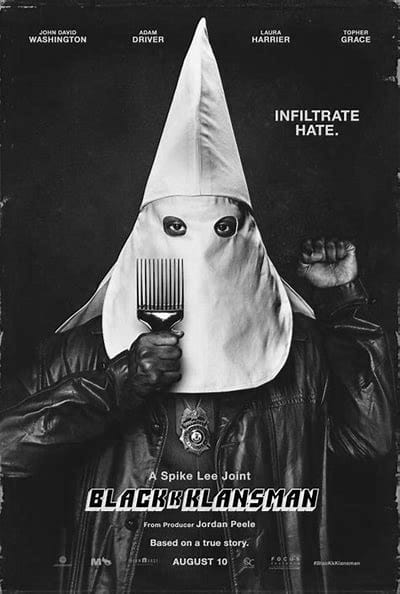

By the end, the film forgets its own subversive formalism and can only repeat the most basic liberal credo that Trump and his people are old-timey racists. This cut from past to present is neither prophecy nor insight, but catch-up: a sorry state for an American master. As it is, “BlacKkKlansman” masquerades as a radical film politically and aesthetically. But underneath, it is just a boring picture wearing a radical mask.

Comments ()