Film Society x The Student: “After Yang”

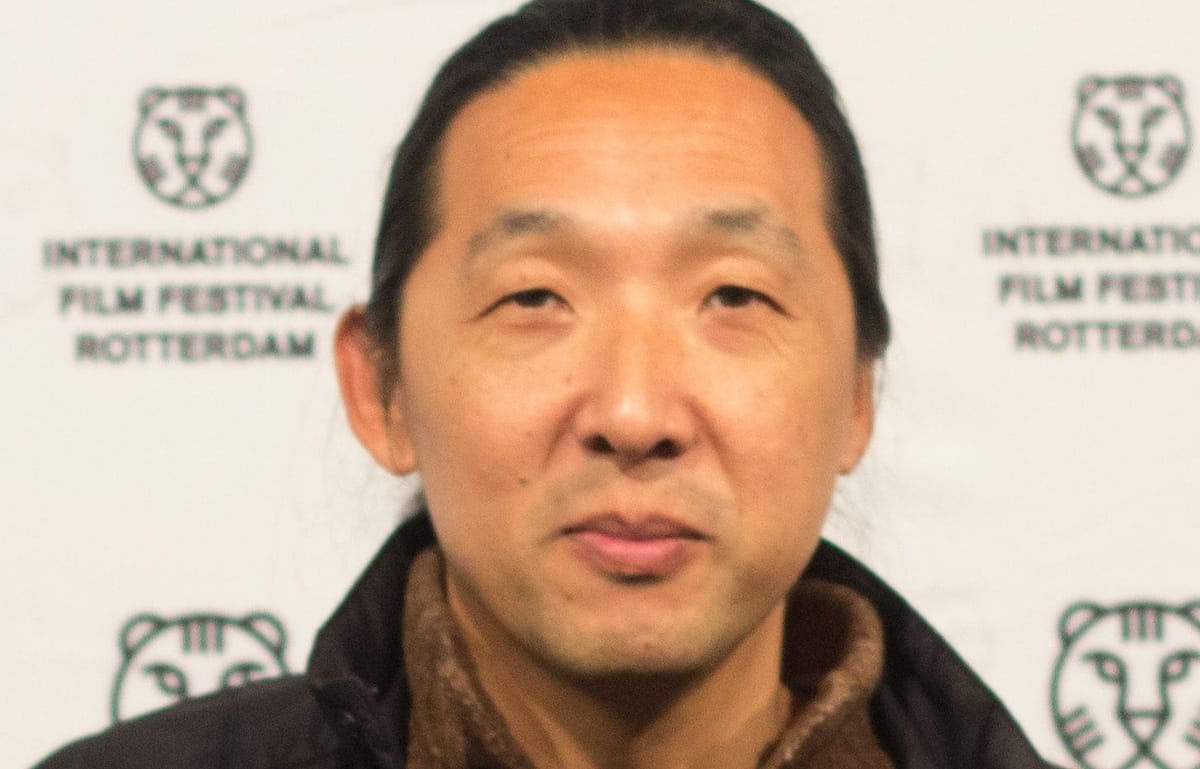

Diego Duckenfield-Lopez ’24 of the Amherst College Film Society explores Kogonada’s “After Yang,” and how the film reimagines common sci-fi tropes of androids to scrutinize social classifications.

“After Yang” is Korean American filmmaker Kogonada’s follow-up to “Columbus,” an understated film with awe-inspiring images of architecture that frame the characters’ exploration of the human condition. In “After Yang,” Kogonada brings this exploration to science fiction. The exploration of humanity is a sci-fi trope that seems almost inherent to the genre, and it’s part of why I love the genre so much. I had doubts that “After Yang” would bring anything new to the table, but it proves to be a unique addition to the genre, questioning not only human identity but the basis of our identities itself.

The film starts with a family taking a picture. The mother (Jodie Turner-Smith) is Black and the father (Colin Farrell) is white, and next to them is an Asian child and a young Asian man. This initial image suggests that the film takes place in a post-racial future. However, we slowly learn that many American racial categorizations still exist in this world. Kyra and Jake’s daughter, Mika, is adopted from China. So they buy Yang (Justin H. Min) — an android from a company called Second Siblings — to teach Mika about Chinese culture and language.

The film explores the aftermath of a sudden malfunction in Yang and how it affects each family member. We learn about Yang through memories — those of his family members, and also Yang’s own, which a repairman discovers in a chip inside his body. The father, Jake, is the one who primarily watches his memories and wonders about the extent of Yang’s internal life — his humanity. This is familiar territory for a sci-fi film, but this film goes beyond simply questioning Yang’s humanity and explores the plasticity of the identities that make us human.

The father, Jake, has a strong prejudice against androids and clones, whom he sees to be less than human. Yang’s memories lead him to believe that Yang thought of himself as human. However, he is berated later in the film for assuming that Yang would want to be human. He learns that it is human hubris to assume that other beings would want to be human. Why must a living being be human in order to be worthy of respect?

In a memory, we see Mika ask Yang about her parentage. Yang decides to take her to a grove with grafted trees. He explains that even though her parents did not conceive her, she is still part of the family tree, just like a branch from one tree that becomes fully incorporated into a new tree. Although I am not a transracial adoptee, this scene stuck with me as a multiracial person who has often questioned the validity of their identity. I have often felt pressure to identify as either Black or Latinx. The grafting metaphor shows the fluidity of identity and that one can be distinct from the original tree but still be fully a part of it. Blood does not determine a person’s identity nor their family.

In a recent conversation on the A24 podcast with Michelle Zauner of Japanese Breakfast, Kogonada discusses the burden of representation put on Asian American artists, noting that he often feels pressure to predominantly represent his own demographic. “After Yang” is Kogonada’s response to this expectation. The film is not as interested in simply presenting positive representations of Asian characters as it is in questioning the social construction of race. In the film, Yang questions his Chinese identity. He asks how he could be Chinese if he has no parents. Is it enough to just look Chinese and know a lot about China? What are the criteria for claiming a racial, ethnic, or national identity — DNA and cultural knowledge?

Kogonada turns the question of humanity back onto the audience. So often in sci-fi, the focus is on androids that want to emulate or become humans. This is usually accompanied by a fear that the androids will want to dominate humans, as seen in films like “Ex Machina,” “The Matrix,” and “Blade Runner,” which are also notorious for borrowing East Asian aesthetics in a way that reduces cultures and people to mere stereotypes. “After Yang” directly confronts the dehumanizing effects of Asian stereotypes in sci-fi and the assumption that humans are the most advanced form of life that can exist, and that anything else would either want to emulate humanity or destroy it, never in between. “After Yang” asks what the world would look like if the line between human and non-human were not so fixed. It similarly extends this question to identities like race, which are not as fixed as we make them out to be. “After Yang” asks us to embrace the ambiguity.

Comments ()