From Crags to Couloirs: Climbing’s Legacy in Massachusetts

In the critically-acclaimed 2018 documentary “Free Solo,” rock climber Alex Honnold scales the 3,000-foot face of El Capitan in Yosemite National Park in four hours, alone, unaided … and of course, without a rope.

The limits of climbing are being pushed every year with ventures like Honnold’s, but as new ascents get harder, taller and more dangerous, our attention drifts further and further from the sport’s humble origins right here in the small cliffs and craglets of Massachusetts.

First, there are two names to remember: Miriam and Robert Underhill. The two met on Appalachian Mountain Club climbing trips in the White Mountains of New Hampshire and soon formed an unstoppable climbing partnership, tackling demanding routes and daring first ascents throughout the Alps during the 20s.

Even after marriage and children, the two continued their climbing streak in the U.S., pioneering new routes in Idaho’s Sawtooth Range and Montana’s Beartooths and completing the first winter ascents of all 48 peaks over 4000 feet in the White — a now highly coveted feat.

Although the Underhills are known as a team, the two were also individually famous for their contributions to alpinism. At a time when women were typically excluded from major expeditions, Miriam was not only climbing the world’s hardest routes, she was also leading them. “Leading a climb” refers to the dangerous task of advancing the rope up a route while periodically placing anchors in the rock (called “protection”) so that the “follower(s)” can later continue up.

Exasperated by the men in her teams who frequently took over in emergencies, Miriam decided to form the world’s first exclusively female climbing teams and put up ascents on some of Europe’s most demanding peaks, including the Matterhorn and Aiguille du Grépon. Robert Underhill certainly has his achievements, too. He single-handedly popularized the now-standard alpine style of climbing during his first major ascents in Europe, the Tetons and the Sierra Nevadas.

But what do the Underhills have to do with Massachusetts? Throughout its near century-long history, climbing in New England has been curiously intertwined with academics and higher education.

Having obtained his Ph.D. in mathematics at Harvard, Robert Underhill stayed at Harvard as an instructor in the math and philosophy departments and participated actively in the fledgling Harvard Mountaineering Club (HMC), founded in 1924.

The Underhills discovered and trained at small suburban crags that remain popular today. You can still find HMC members and MIT Outing Club groups top-roping at the Underhills’ old haunt, Quincy Quarries.

Bringing the history of rock climbing back to the Pioneer Valley (and a little bit of Alaska too), the next names to remember are Dave Roberts and Jon Krakauer.

Roberts climbed some of Alaska’s most challenging peaks before the age of 25, but his talents reach further. Another academic alpinist, Roberts graduated from Harvard (where he too was a member of the HMC) and went on to obtain his Ph.D. in English, publishing the first of his many successful books, “The Mountain of My Fear,” in 1968.

Two years later, he turned in glaciated peaks for cow-spotted fields and took a job teaching English at the recently established Hampshire College.

In his time at Hampshire, Roberts founded the college’s robust outdoors program with a special focus on rock climbing. He introduced students to top-rope climbing at Rattlesnake Gutter, a crag in nearby Leverett, Massachusetts, and brought the more precocious climbers on ambitious trips to Colorado, Utah and obscure Alaskan ranges.

Roberts’s expeditions with this infant liberal arts college were competing with the decadently-funded Ivy League mountaineering clubs at Harvard and Yale. Turns out the 40-foot cliffs of the Pioneer Valley provide good practice for the 3,000-foot spires of the Arrigetch Mountains in Alaska.

You might have heard of one of Roberts’ more talented pupils: Jon Krakauer. An accomplished mountaineer and the author of famous works of outdoor literature “Into the Wild” and “Into Thin Air,” Krakauer credits Roberts with sparking his passion for everything alpine, both in the classroom and at the crag.

In addition to his literary achievements, Krakauer has summited some of the toughest routes in Alaska and the Andes, and established a first ascent of Rakekniven in Antarctica with climbing legends Alex Lowe and Conrad Anker. This stunning career all began 15 minutes away from Amherst in Leverett.

Roberts’ renowned outdoors program at Hampshire has unfortunately shifted its focus away from climbing in the past couple of years, but it remains a popular sport in the Pioneer Valley, with plenty of outing clubs, outdoors programs, Facebook pages and nonprofits dedicated to its maintenance.

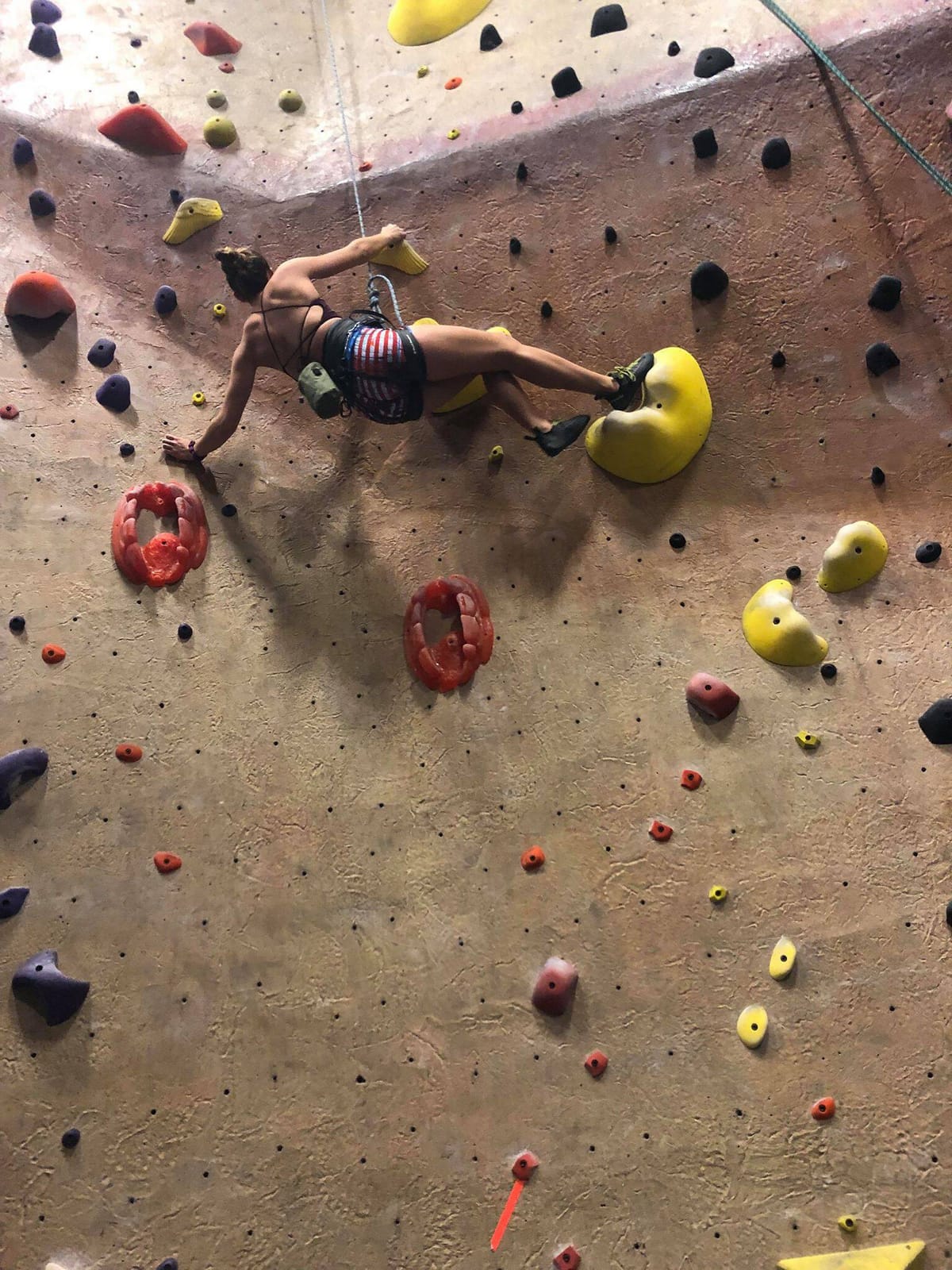

Here at Amherst, we have the Amherst College Outing Club (ACOC). For students of various levels of experience from the beginner to the expert, regular trips to the nearby Central Rock Gym in Hadley are announced on the climbing Facebook page and are free to students — no experience or gear necessary.

For the more experienced (or adventurous) climbers, ACOC organizes outdoors climbing trips to nearby crags, such as Farley Ledges, the Sunbowl (accessible via the PVTA!) and Mormon Hollow.

On these trips, students can learn the basics on top-ropes, and more ambitious climbers can lead their own routes. For more frequent outdoor trips, the outing club at UMass Amherst also organizes trips to local crags and opens its activities to students of the five colleges.

Outside of the five colleges, the Western Massachusetts Climber’s Coalition (WMCC) is a nonprofit organization that helps coordinate with landowners for public access to Western Massachusetts’ most popular crags. WMCC also organizes public events and classes to help educate beginners and connect seasoned climbers.

Massachusetts, higher education and rock climbing are intertwined in a rich history and vibrant present. Who knows? Maybe the next daredevil to climb El Cap without a rope will be able to proudly claim that Amherst College taught them how.

Comments ()