Indigenous Students Reflect on Community, Identity and Need for Change

The Student interviewed members of the Native and Indigenous Students Association (NISA) on their experience at the college in light of Indigenous People’s Day on Oct. 11. Interviewees discussed community, identity and the changes they hope to see in the college going forward.

In light of Indigenous People’s Day on Oct. 11, The Student spoke with members of the Native and Indigeous Students Association (NISA) to gather perspectives on the experience of being Indigenous at Amherst. Interviewees discussed the role that community plays in their lives, as well as how they hope to see the college change. The thoughts shared in this piece are neither representative of an entire organization, community or experience, but rather individual perspectives to be amplified in the wider campus community.

Finding Community

For many Indigenous students, the very act of attending an institution like Amherst is one that is deeply conflicting. As Emma Cape ’22 — a member of the Delaware Tribe of Indians and Minnesota Chippewa Tribe, and NISA social chair and social media manager — put it, Indigenous students often have to navigate between a discomfort with being “at a place that we know quite literally was built without us in mind” and a pride for “walking around this place, knowing that I’m not supposed to be here.”

Jacquelyn Cabarrubia ’25, a member of the Odawa-Little River Band of Ottawa Indians and member of NISA, echoed the sentiment, sharing her own difficulties: “As an Indigenous woman who has grown up around Native Americans my entire life, it is heart-aching being in a place where my culture and traditions are not encouraged. In a lot of ways my identity feels suppressed. There is no comparison I could share to relate even a sliver of what it feels like to be here.”

The specter of Lord Jeffery Amherst — the college’s unofficial mascot until 2016 and implicit namesake — also looms large for many due to his role in biological warfare and the genocide of Indigenous peoples. Although appreciative of the tight-knit Indigenous community that has grown on campus, Cole Richards ’22, a member of the Cherokee Nation (Oklahoma) and NISA’s executive officer, find herself constantly grappling the college’s status as “this hyper-colonial institution based on the name of someone who is genocidal, and who gave my tribe, specifically, smallpox blankets.”

“It’s kind of hard because I feel all this amazing goodwill towards my fellow Native students and a lot of people and the professors in American Studies who do a lot of amazing stuff, but then I walk past Amherst College and see that name and it just brings up a lot of feelings — because, genocide, and genocide of my tribe, specifically,” she added.

Still, the importance and the strength of the Indigenous community on campus — and NISA in particular — was something that many interviewees cited as pivotal to helping them work through the contradictions and barriers faced by being Indigenous at Amherst.

“[NISA] is like a community outside your community. It’s so special,” said Carley Malloy ’22, a member of the Citizen Band Potawatomi Nation and co-president of NISA. “NISA has been a place to just be.”

Cape concurred, reflecting on how NISA helped her to be “her full Indigenous self.” “[NISA is] a space and a community with whom I can be unapologetically Indigenous. That is really important for me,” she said. “Growing up, it was never something that I hid, or was ashamed of by any means, but historically within my family, it’s been an identity with which people have had to be very careful, to protect one’s well-being in a predominantly white town.”

Members of NISA also emphasized the diversity and multivocality of their experiences, and how that shapes their community. Sage Innerarity ’22, a member of the Ione Band of Miwok Indians and co-president of NISA, noted: “[NISA] is a place where, even though we all may come from different tribal nations and different places, we understand what it’s like to be Native at a place like Amherst. [Yet,] more important than our ability to understand and share our experiences and struggles is the amount of love, support and celebration we create and provide for one another.”

“It’s been a really validating space where I feel like I can meet people outside of my class year,” added Alexis Scalese ’22, a member of the Pueblo of Tue'i (Isleta) tribe and NISA vice president. “I really like NISA for that, because it really does feel intergenerational, in a way.”

NISA’s Priorities

Given NISA’s role in helping Indigenous students navigate Amherst campus, the group is working to strengthen its community for present and future generations of Amherst students.

One thing that the group commonly reflects on and accounts for, Scalese said, is “what it means to accommodate different viewpoints and recognize them within our own community. We are not all the same,” they said. “We have our own different belief systems within our own communities … We’re from different regions around the U.S. and outside the U.S. too,” Scalese said.

Some of the tribes that Amherst students belong to include Southern Ute, Yup’ik of Nelson Island, Chamoru, Native Hawaiian, Assonet Wampanoag, Iroquois Nation, Apache Tribe of Texas and Mohegan and Minnesota Chippewa Tribe.

Richards also emphasized the importance of recognizing that Indigenous communities are not a monolith. “Being Indigenous is not one thing,” she said. “We are here together, but there have been a lot of instances where there is a really broad generalization of what it is to be Indigenous.”

Along these same lines, Cape reflected, “There is not one way to be Indigenous — if you don’t fluently speak your traditional language, that’s okay; if you didn’t grow up in your traditional homelands, that’s okay too. It doesn’t make you any less Native, despite what popular culture and Western society might think or say.”

The group has also prioritized growth over the past several years. “The year before we got here [2017], NISA only had about five people. Now we have 25 or 30 students,” said Malloy.

NISA’s Activism

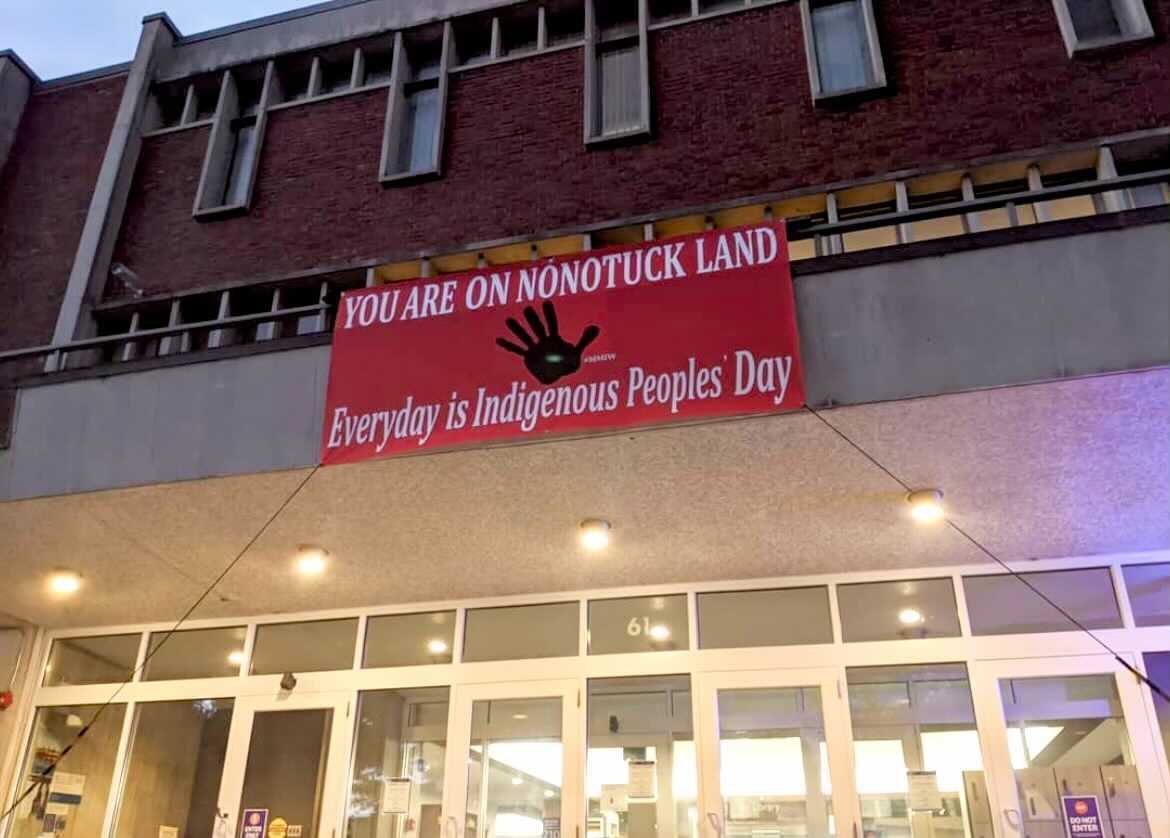

NISA’s activism this semester has involved tabling in Valentine Dining Hall to spread awareness about The National Day of Truth and Reconciliation, or Orange Shirt Day, to honor and remember those impacted by residential schools in the United States and Canada. The group ended up raising over $2,000 from the campus community, which they donated to the Orange Shirt Society, Indian Residential School Survival Society, The Gord Downie and Chanie Wenjack Fund and Creation of an Anishinaabe Round House. In addition, the week before Indigenous People’s Day, the group hung a banner in front of Frost Library that reads “You are on Nonotuck Land.”

Hanging this banner to commemorate Indigenous People’s Day holds different values and importances for different members of NISA. “[Indigneous People’s Day] is a time to celebrate our [survival], though such celebration isn’t relegated solely to this day,” said Innerarity.

Cabarrubia echoed: “Indigenous People’s Day is so much more than a day — when the day is over, we are still Indigenous. We are proof of what couldn't be erased through residential schools, attempted genicode, broken treaties and forced assimilation. We are still here.”

The symbolism this banner holds thus made it all the more upsetting for Indigenous students when it was found torn down the morning of Oct. 17. The incident left many students of color, particularly Indigenous students, reporting feeling shaken and unsafe.

“It was really unfortunate to see that banner ripped,” said Scalese. Malloy added: “I don’t think [the incident] was racially motivated — I think they were drunk and being stupid. But regardless, when something is mentioning race in it, it is unsettling to have it torn down.” Similarly, Scalese said, “Because [the banner] is something that is racialized, it is therefore a racist act.”

Malloy and Scalese attested that they would like to see the college community step up and rehang the banner without requiring further labor from Indigenous students. “I don’t think we should have to put in the work to make a new one. We already did that,” said Malloy. “It did make my heart happy to see that message in the [campus-wide GroupMe] chat that said ‘Indigenous people should not have to do this,’” said Scalese, adding that they hope that whoever tore down the banner will take steps to educate themselves, perhaps by taking a Native studies class.

Demands for Institutional Change

Seeing the institution take responsibility for its wrongs against the Indigenous community goes beyond just amends for this incident, students testified, especially in light of the recent Bicentennial celebration. Scalese said, “For me, [support] goes beyond saying ‘Indigenous People’s Day.’ This school still has stuff they have to deal with. We need to address things, like the Indian Relic Museum that is now Appleton [Hall]. That is not recognized. You don’t see that at the Bicentennial,” they said. “We don’t have to celebrate everything about this school. We can celebrate and critically examine what has happened in the past.”

Emma Rial ’22, a member of the Narragansett Indian Tribe and member of NISA, also found the Bicentennial Party to be, Rial added, a symbol of the college’s lacking accountability to its history. “The very existence of Amherst College on Nonotuck Land is a reminder of the erasure of Native communities.” In celebrating the history of Amherst and recreating the college’s “founding,” she said, “what Biddy, the Trustees and prestigious alumni networks celebrated ignored the larger history of local Indigenous communities and how they are impacted by the college’s presence.”

Students also emphasized the importance of incorporating Indigenous knowledge and ways of thinking into learning at Amherst. “There’s very little non-Western thinking in classes, very little acknowledgment of place and identity, especially in STEM,” said Malloy. “I think there is a lot of work the administration and professors have to do to be more aware of how dynamic we are, and how we are going to continue growing. This is going to require some changes to the curriculum.”

Zoe Callan ’25, a member of the Navajo Nation and member of NISA, similarly expressed: “I think something the community as a whole could be doing better is hav[ing] more Indigenous perspectives included in classes not necessarily focused on Indigenous topics.”

This lack of a framework for Indigenous thinking in class materializes in harmful experiences for Indigenous students in the classroom, some recounted. “Something that is very basic and something that should go without saying, but that unfortunately needs to be said, is speak about us in the present tense,” said Cape. “I can’t tell you how many times I’ve been in class, and professors know I’m in this class, and they’re sitting there using past tense forms, and it’s incredibly frustrating.”

Language and terms matter, she continued. “Call us what we want to be called… I know most people prefer their specific tribal affiliation… I’ve also been in classes where my professor will not stop using the word ‘Indian,’ and once again, I am right there… Being cognizant of those sorts of things, I think, is a baby step in the right direction.”

This would also help with general education of the student body. “There are a lot of instances where I am called upon to educate my non-Indigenous peers, sometimes on issues I am not familiar with,” said Callan. “I wish the community here at Amherst took it upon themselves to learn more about these issues on their own and to not expect every Indigenous person to be well versed in every Indigenous issue or custom.”

Scalese added that they would like to see the administration more completely recognize NISA as an affinity group. “Affinity groups across campus recognize us, but sometimes the administration doesn’t really see us as a community that has more than five people,” they said. “We are growing, and it’s a pretty recent growth, so I understand why that narrative might be out there, but I feel like it’s time to acknowledge and recognize.”

For some, alongside the hope for restructuring and change comes an appreciation for the resources offered through the college and the empowerment it sometimes provides. “Personally, in a lot of ways, this has been a great institution [for me],” said Malloy. “Amherst has so much money, they could bring me here, and I could learn from Native professors and I could learn alongside amazing Native people.”

Scalese views these resources as a path for ultimately helping communities outside of Amherst. “I don’t believe that this school will ever be designed to serve Native students because at the end of the day, this school was built off of stolen land and benefits from that every single day,” they said. “However, I do think there are ways — we are making ways, staff members are making ways, faculty are making ways — for us to come back to our communities, come back to where we want to be, be people who we want to be to make Indian Country better and to use the resources at the school to benefit people who are outside of the school… [this is the] commitment that some of us share to be nation-builders, and uphold our tribal sovereignty outside of the school.”

These shifts in thinking, perhaps, are part of the broader narrative around a changing Amherst. “This isn’t a white school anymore. It isn’t just white, upper-class,” said Malloy. “Now, professors have to put in the work — just as we do to be recognized — to recognize and talk to us and think about how they can create a more inclusive place.”

The land on which Amherst College sits is Nonotuck land, with the Nipmuc and the Wampanoag to the east, the Mohegan and Pequot to the south, the Mohican to the west, and the Abenaki to the north.

Comments ()