“No Other Choice” South Korean Movie Review

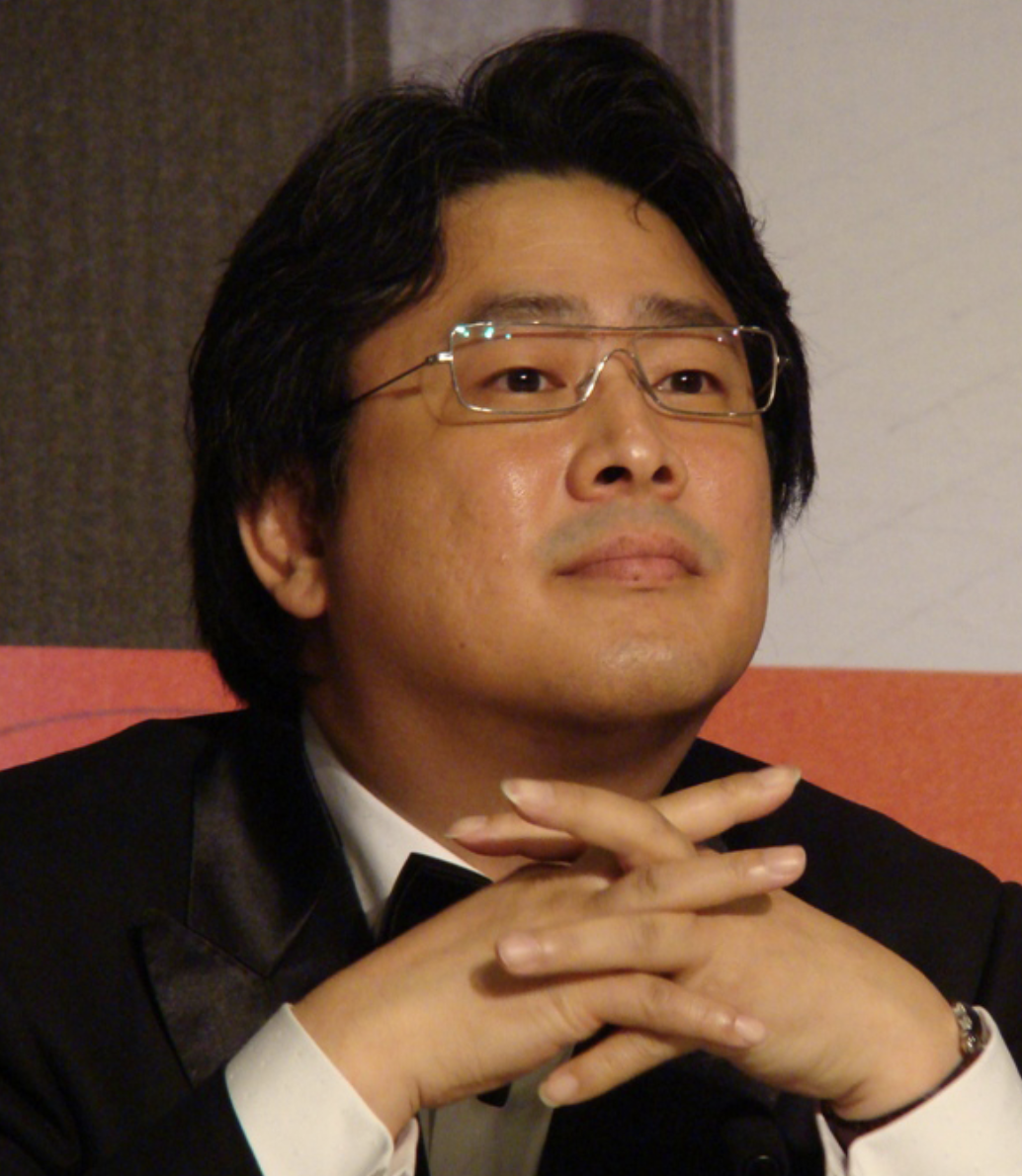

Fresh off its Golden Globe nominations, the 2025 film “No Other Choice” gets a compelling review from Editor-in-Chief Edwyn Choi ’27, who unpacks the film’s chilling mix of horror and irony, as well as the technical elements that deliver its emotional punch.

If there’s one thing that Amherst students are always anxious about, it’s everything we have to do to feel safe in a job market hemorrhaging workers by the day: internships, networking, begging professors to round up our final grades. It often feels like we have — to borrow from Park Chan-wook’s latest film — “No Other Choice” but to forever compete in the capitalist rat race.

Borrowing its source material from Donald Westlake’s 1997 novel, “The Ax,” and functioning as a remake of Greek-French director Costa-Gavras’ 2005 film adaptation of the same name, “No Other Choice” (어쩔수가없다) follows 25-year paper industry veteran Man-su after he gets fired from his company, Solar Paper. Man-su is fired because Solar Paper has just been bought out by Americans, who immediately begin massive layoffs. When he tries to plead with one of the buyers near the beginning of the film, he’s told that they had “no other choice.”

Characters constantly repeat this mantra to themselves, and Man-su is no exception: unable to support his family, he tells himself that he has “no other choice” but to kill his competitors so employers will hire him instead. He lures his victims in with a fake job advertisement and spends the rest of the film eliminating the ones who have better resumes than his.

But don’t expect anything resembling the likes of Martin Scorsese’s “The Departed” (2006) or David Fincher’s “The Killer” (2023): There’s less action than what the description suggests. In fact, much of the film’s attention is instead devoted to Man-su’s crumbling family life, which (for the most part) is anything but thrilling. His wife, Mi-ri (Son Ye-jin), puts up the house and other material possessions for sale, not to mention the fact that she takes Man-su’s prolonged absences during his first murder as a sign of infidelity. Man-su’s teenage stepson, Si-one (Kim Woo-Seung), commits petty theft to raise money, and his younger daughter, Ri-one (Choi So-Yul), who is a neurodivergent cello prodigy, has to quit her lessons.

These basic plot points, however, don’t cover the film’s intelligence and humor. Park isn’t afraid to have his movie rapidly switch between funny, depressing, scathing, and even grotesque at times. This rapid switching underscores the sharp commentary and moments of irony Park has baked into his film. For instance, Man-su has a passion for gardening despite his job in the paper industry.

Of course, things go deeper than just irony and juxtaposition. The film quietly develops a running list of objects and problems that all eventually tie back to American influence on South Korea: Man-su’s career is jeopardized because of a buyout from the Americans; he has a nuclear family, a model popularized by the United States; his weapon of choice is his father’s pistol from Korean involvement in the Vietnam War; there’s a costume dance where Mi-ri dresses up as Pocahantas, a critique of cultural commodification that also recalls Bong Joon-ho’s 2019 film, “Parasite”; and, on a broader note, because South Korea’s political and economic systems developed under U.S. influence, critiquing the system implicitly critiques that influence.

But the film’s subtle commentary on American intervention in Korean history isn’t immediately obvious, and media attention has instead been devoted to its commentary on Artificial Intelligence (AI), which is introduced at the film’s end. Without any major spoilers, all I can say is that the introduction of AI adds a subtle but terrifying twist to the film’s meditation on capitalism.

It’s important to note, though, that what I’m describing as a twist is mainly thematic — there are no major plot twists here like we’ve seen in Park’s previous movies. Nothing, for instance, like what waits for you at the end of “Oldboy” (2003) or the back-to-back twists in “The Handmaiden” (2016), two of Park’s most critically acclaimed films. This is a straightforward plot with a brilliant execution (no pun intended): Man-su kills more competitors until he has no one else to compete against.

What does carry over in “No Other Choice” from Park’s previous work is the intelligent direction and sound design. There are few films that blend technology into the camerawork as well as this one does, never mind all the visually striking direction one can always expect from Park: One shot was from the bottom of a beer jug while Man-su drank it all in one go (you can see what I mean in the trailer). Also expect an incredibly diverse soundtrack: Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 23, “Redpepper Dragonfly” by Cho Yong-pil, and “Hold On, I’m Coming” by Sam & Dave, among others.

While this film is one of Park’s best, there are some pacing issues. It felt as though the death of Man-su’s second victim was rushed, even if this victim arguably has the furthest-reaching consequences in the film. The film’s first half is also noticeably more chaotic than its latter half, mirroring Man-su’s increasing efficiency as a killer, but that transition from chaotic humor to chilling seriousness might lead to a disappointing experience for those who want the grand, maximalist payoff we’ve seen in Park’s prior films. “No Other Choice” doesn’t do any of that. It just decompresses.

But maybe it’s this decompression that Park wants us to sit with, the absurdity and horror of spending your adult life climbing the corporate ladder, the twisted actions and sacrifices you’ll have to make to climb even higher. There are no answers once we reach the top, Park seems to be saying. All we have is more work and less time.

Comments ()