Remembering the Life of Spencer Williams ’24

Spencer Williams ’24 made his mark on the college as a friend, a student, and a writer. Amid lengthy cancer treatments, Williams found solace in connections with others.

Spencer Williams ’24 died last week, more than two years after he was diagnosed with a rare form of brain cancer.

Friends and former professors spoke to his passion for debate, soft-spoken and witty demeanor, talent as writer of both prose and poetry, and grace following his diagnosis in the fall of 2021.

Williams was a voracious reader, often reading, and quickly finishing, multiple books at the same time. He loved “cutesy things” — dogs, miniature stuffed animals, and the chickens and ducklings he and his mother raised at their home in Portland, Oregon, said friend Allie Ho ’24.

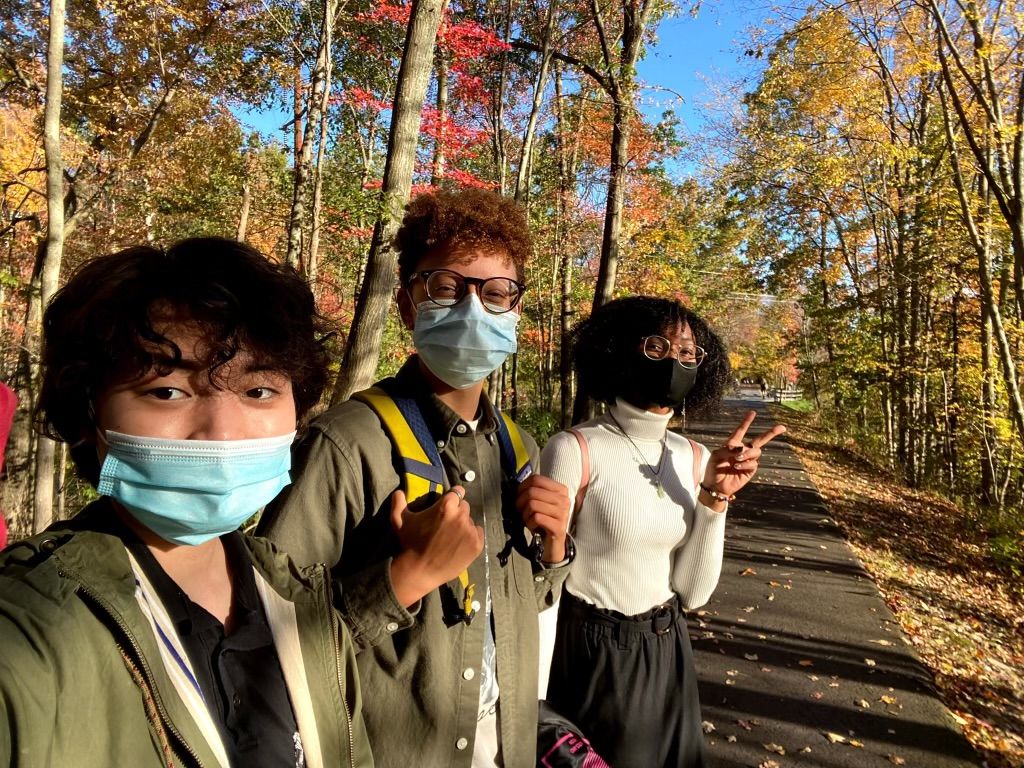

When he wasn’t reading, Williams filled his first year at Amherst with explorations of Book and Plow farm, walks in the bird sanctuary, and cooking nights with his friends.

“He was a quiet kid. You had to get to know him a little bit,” said friend Claire Jensen ’24. “Everything he said was very eloquent, very thought out … He was very intelligent, really hilarious, like really funny.”

Though he only completed two semesters before his diagnosis, Williams made a mark on Amherst, serving as the president of the Chinese Student Association, writer for The Indicator, and a community advisor for the Asian Culture House. Williams also competed as a member of the Harvard University debate team.

Jensen and Williams were both part of the Trans Connection Project, where small groups of students met to talk about their experiences as queer people while getting to know Amherst. Williams looked forward to taking Trans History with Winkley Professor of History and Political Economy Jen Manion.

“It was really exciting for him to be able to be a trans person learning about his history in an academic context, where there historically has been a lot of erasure,” Jensen said.

Later, Williams researched hiring bias toward binary and non-binary transgender people under then Visiting Professor of Psychology Rebecca Totton.

Even as he left campus to pursue treatment at a series of hospitals across the country, Williams stayed connected to the college, texting with friends, posting updates on social media, and publishing a heartfelt discussion of his experiences with cancer in The Student.

“There were a couple times when he would text me: ‘Hey, Claire. I’m hoping to come back to school next semester,’” Jensen said. “And that never happened. I think that took a bigger toll on him than he let on.”

Williams remained close with Austin Sarat, professor of jurisprudence and political science.

“Spencer Williams was an extraordinary student in my first-year seminar,” Sarat said. “From the first encounter with Spencer, there was something distinctive about the way in which he thought and the way in which he spoke. He was incredibly imaginative.”

Sarat remained in contact with Williams and his mother almost daily during the more than two years he was away from campus receiving treatment.

“Spencer displayed extraordinary grace and gratitude — grace and gratitude towards the people, the doctors, who tried to help him, and grace and gratitude towards me,” he said. “So even as he faced the prospect of his own passing, he was still concerned about other people.”

Ying Sun, Williams’ mother, said that towards the end of his life, Williams opted to continue receiving a grueling experimental treatment involving CAR T-cells, even as doctors offered him the choice of palliative care.

But Williams chose to continue, saying, “‘First, I want of course to get well, but secondly, I also want to help the other children,’” Sun remembered.

“He wanted the doctors, the nurses, to learn from him,” she added.

Through two years of sometimes exhausting treatments that included three brain surgeries, Williams continued to pursue his passions.

He continued to coach and judge high school debate. He interned for a state house campaign in his home state of Oregon in the fall of 2022. He traveled to Japan and China with his mother, worked to complete a personal bucket list, and spent time with his boyfriend in Portland.

Through it all, Williams fondly remembered his time at Amherst and hoped he would be able to return.

“He wanted to experience fewer restrictions [post-Covid] and the Amherst community because he really did find a good tight knit group of people,” Jensen said. “He was really academically stimulated and excited to pursue his passions.”

However, he and his mother criticized the way the college handled his illness.

In a March 2023 article in The Student, Williams recounted his experiences at the college leading up to his diagnosis, which included multiple trips to Keefe Health Center where his symptoms were largely dismissed, an instance in which he was stranded at Cooley Dickinson after an ambulance took him to the emergency room, and a time when he was bedridden but school policy prevented his friends from bringing him food.

Sun also said she was never notified that Williams was having health issues, even after he had been taken to the emergency room three separate times. She also said that, beyond messages from Sarat, she received no word from the college following Williams’ medical leave.

“We did not get any phone call, or any message, or any email ask[ing] how Spencer’s doing,” she said. “I just hope this [does] not happen to other students in the future.”

Beyond a discussion of his time at Amherst prior to the diagnosis, Williams’ article in The Student was also a broader reflection on the reality of life with cancer.

“I remember the first time I read [Spencer’s] article, I was in Antonio’s, and I broke down crying, and then I sent it to a whole bunch of people,” said friend Kobe Thompson ’24. “It was a wonderful exploration of his feelings on the matter. It was very deep.”

Thompson added that, as he grew closer to Williams from afar as he underwent treatment, it didn’t strike him to remember “every detail and every moment.”

“I thought they were just small drops in the grander ocean of memories I would have with him,” he said.

Despite the pain of the treatments and the weight of the diagnosis, Williams and others spoke to the ability to find beauty and connection amid suffering.

“I’d never had the privilege of accompanying a student as they went through the kind of experience that Spencer went through,” Sarat said. “And the word I use, I mean. It was a privilege. In the end, a heartbreaking privilege, but it was a privilege to be a part of his life as he went through the treatment that he had to go through.”

In his article in The Student, Williams wrote that he chose to focus on “the overwhelming kindness in [his] darkest moments.”

“Cancer is a sword, but it is also a reminder of human kindness, of soft touches and quiet connections,” he wrote. “When I die, whether that be in five years or one hundred, may I have lived tenderly and lovingly, fluffy with empathy and heart. Amid the genetic mutations and surgery scars, there is an undeniable beauty that traces the preciousness of my single human life.”

One of Williams’ poems for The Indicator, “Ecology of a Beach House Love,” was reprinted for this week’s edition.

Comments ()