Russian Scholars Evaluate Opposition Leader Alexei Navalny’s Life and Legacy

Panelists at a Feb. 26 roundtable analyzed the late opposition leader’s unique appeal and discussed what his life and death indicate about the political realities of Vladimir Putin’s Russia.

Four of the college’s visiting Russian scholars participated in a Monday, Feb. 26 roundtable on the life and legacy of Alexei Navalny, the Russian opposition leader who died under suspicious circumstances in a Siberian prison earlier this month.

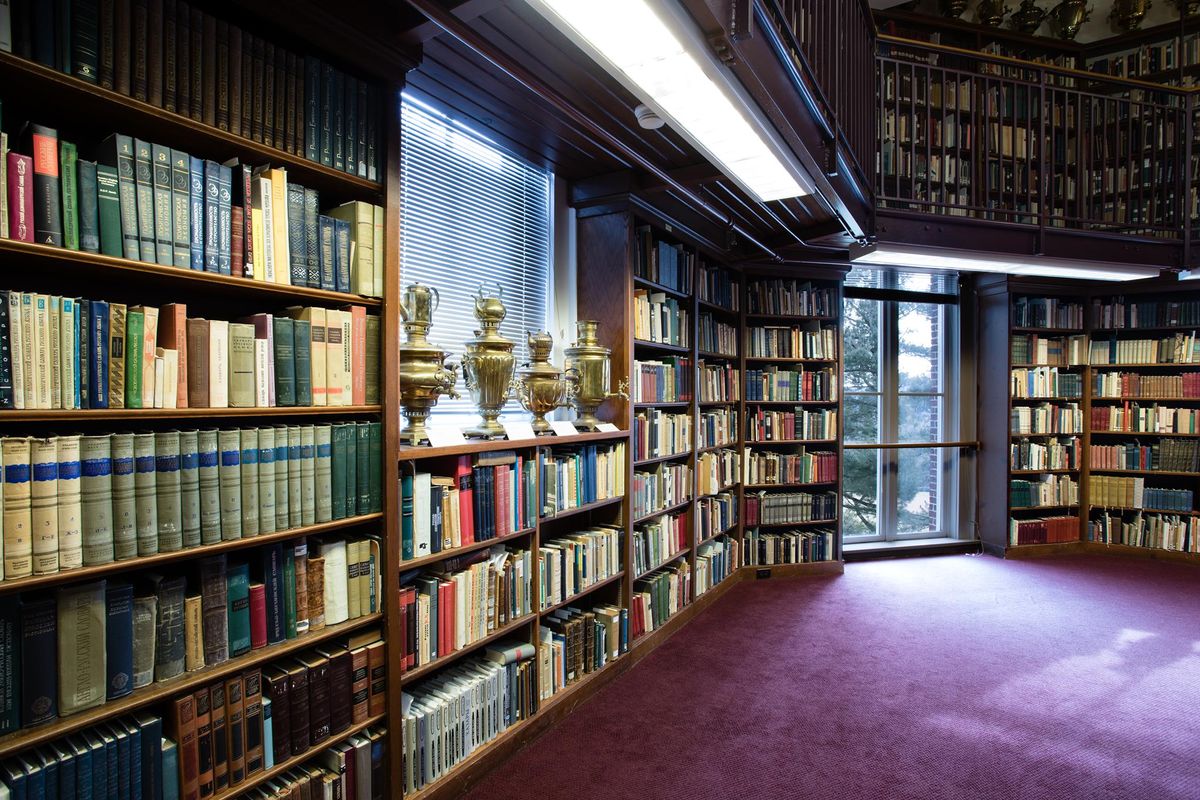

Surrounded by the Amherst Center for Russian Culture’s floor-to-ceiling collection of Russian books and following a short excerpt from a 2022 documentary about Navalny, the speakers discussed what his life and death revealed about the political realities of Vladimir Putin’s Russia.

Some emphasized the shock and emotional resonance of Navalny’s death. Organizer Michael Kunichika, chair of the Russian department, compared its gravity to the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. or Robert Kennedy.

“Many of my friends described his death as something [similar to what] they experienced when a close friend of theirs died,” said a panelist who chose to remain anonymous to protect family members living in Russia.

Navalny was Putin’s most outspoken critic, known for his series of high-profile yet unsuccessful electoral campaigns, charismatic social media presence, and viral videos exposing the corruption of the Russian elite.

His advocacy led to a number of arrests and a 2020 poisoning at the hands of the Russian government that nearly killed him. Now, the exact cause of Navalny’s death remains unclear.

Panelists, including Alexander Semyonov, John J. McCloy ’22 visiting professor of history, also discussed Navalny’s unique appeal and contributions to Russian politics.

“He really pioneered a very different style and genre that was not coming out of preconceived principles, but that was a response to situations,” Semyonov said.

“The real innovation is in bringing politics down … to the local level,” Semyonov continued. “The real threat of his platform [was] a network of regional centers, which if you look very carefully, never shared a common agenda.”

The anonymous speaker, an art history specialist, discussed Navalny’s visual style. It featured simple fonts and bold colors that signaled a brighter future for Russia’s youth while echoing Soviet imagery and early-20th-century futurist art.

They also highlighted Navalny’s ironic sense of humor and command of digital mediums.

“By presenting the corrupt officials and killers as people who can be mocked … he really made these investigations which would otherwise be unbearable not only bearable, but also at times funny,” they said.

Multiple speakers acknowledged that Navalny was a controversial figure, even among the Russian opposition. Early in his career, Navalny was associated with a far-right, anti-immigrant stream of Russian nationalism, a movement he distanced himself from over time.

“That’s the nature of human politics,” said Semyonov. “He made these errors. But for me, what is important is how he learned and how he evolved out of this initial charismatic leadership.”

Though all acknowledged Navalny’s charisma and political innovations, multiple speakers addressed the question of whether Navalny had “miscalculated,” of why he had returned from exile to what in retrospect seems like a certain death, and why his movement had ultimately failed to undermine Putin’s regime.

Maria Mayofis, a visiting research fellow at the college, attributed Navalny’s lack of success to his focus on the issue of corruption.

“The investigations themselves were made brilliantly. They were captivating,” she said of Navalny’s massively popular YouTube series on the corruption of Russia’s elite. “But the audience was already used to widespread corruption and widespread violence, they considered both normal. And this normalization would be the reason why this online audience was not converted to real support in Russian big cities.”

Ilya Kukulin, the fourth member of the panel and a visiting research fellow, argued against the notion that “the Russian people are incapable of standing up against [their] government.” He suggested that Navalny, however, was too optimistic in hoping for rapid changes in the minds of non-Westernized groups of Russia’s society.

“One of the reasons [for his lack of mass support] is precisely because Navalny behaved like a Western-style politician fighting for votes,” he said. “There’s a considerable number of people of elder generations in Russia who do not see politics as an electoral process. From their point of view, political power consists of a group of people who are engaged in the production and centralized distribution of the meaning of life for the whole population.”

The speakers generally agreed that the future of the Russian opposition was bleak.

“The Russian pessimist says, ‘It is so bad, it cannot be worse,’” joked Semyonov. “And the Russian optimist says, ‘Oh sure it can.’”

At the same time, the speakers said it was possible that Navalny had planted some seeds of hope for the future.

“Navalny has contributed greatly to spreading the very idea of legalistic and competitive public politics among the Russian youth,” Kukulin said. “I hope that the notion that competitive politics are still possible in Russia will have a delayed effect.”

He also said he believed that Putin’s public and obviously personal hatred of Navalny would, over the long term, delegitimize his regime.

The anonymous speaker closed their presentation on a hopeful note, displaying images of Navalny with his wife Yulia, who many expect to take up her husband's role as head of the Russian opposition.

Their final slide showed one of the last photos taken of Navalny, laughing at a judge during a virtual court hearing the day before his death.

“I really hope that this positive image, this lively image, will continue to inspire Russian people and not only Russian people, but everyone who's fighting against Putin’s regime and other oppressive regimes,” they said.

Both attendees and organizers said they got a lot out of the discussion.

On student in attendance, who asked to not be named, said he attended the event to gain more information after an Amherst Political Union discussion about Navalny’s death. He had seen the 2022 documentary, but said that the discussions’ more neutral, analytic approach added to his understanding of Russian politics.

“[The panel] introduced a whole host of critical perspectives that one is not exposed to if one watches [the documentary], because it's a political product,” he said. “As much as one can respect and revere Navalny, that does limit how you can think about and perceive Navalny and movements in Russian cultures and society.”

The 2022 documentary “Navalny” will be screened in the Keefe theater on Wednesday, Feb. 28. There are screenings at 4:30 and 8 p.m.

Correction, Feb. 28, 2024: An earlier version this article included the name of a student who subsequently asked to remain anonymous.

Comments ()