Speaking About the Election Results in a Post-Moonlight America

The following review of “Moonlight” contains spoilers.

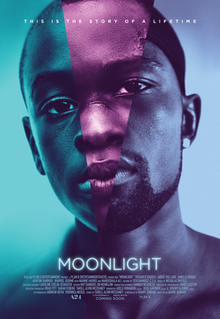

“Moonlight” was released on Oct. 21. The film, directed by Barry Jenkins and written by Tarrell Alvin McCraney, debuted at the Telluride Film Festival and has been swimming in critical acclaim since. The film follows the story of Chiron, a black boy, and then man, growing up in a rough neighborhood in Miami. Chiron’s development is depicted in three different stages of his life, manifested as the film’s three chapters. The three stages shift as Chiron’s relationships shift, giving rise to three separate, but fluid versions of himself. In the first chapter, titled “Little,” a young Chiron is played by Alex Hibbert. It’ll be the young actor’s first IMDB entry, but the part was aptly cast. Teenage Chiron is played by Ashton Sanders, who has been featured in a few films, including a very minor role in “Straight Outta Compton.” In “Black,” the film’s final chapter, Chiron is played by Trevante Rhodes, who will be a familiar face to “Westworld” fans. The film also features popular vocalist Janelle Monáe, Naomi Harris and Mahershala Ali, best known for his role as Remy Danton in “House of Cards.”

The plot, following Chiron as he works through his identity, is beautifully written and thoughtfully delivered. To tell this story — one of a black boy in Miami grappling with his sexual identity, his mother’s crack addiction and the flux of human connection in his life — in such a delicate manner is an incredible feat. And rightfully so, the rise of “Moonlight” has been steady. I’ll stop my conventional review there, as there’s no point in wasting time reiterating the dozens of reviews that have trickled in, dubbing “Moonlight” the film of the year. If you want to read a review detailing the technical and thematic elements that render “Moonlight” a success, look no further than the critics that get paid to do so — The New York Times and The Atlantic have all accomplished this recently.

Instead, I’d like to detail why I have found this film so beautiful in post-election America. After all, a film is always released into a certain historical context. Something I’ve been digesting in the days following the election is the notion of the limitations of language. For me, the phrase “my words fail me” have never rung more true. In the hours, days and weeks following Donald Trump’s election, words have been spoken, screamed, typed and flung from every direction. They have risen in solidarity, in protest and in explanation. But what I’ve been noticing is that so many of us, me included, have fallen back on comparative language. Metaphor and simile: from classmates, friends, professors and family alike I’ve heard “this election feels like heartbreak,” “it feels like something has died,” “some metaphor detailing the joy of a Trump supporter, because I’m having trouble thinking of one on my own.” We’ve never had an election like this, so we turn to comparison. I can’t tell if this is because we don’t know how to aptly name what we’re feeling, or if its because we’re afraid to. Regardless, words fail. Like-minded individuals have been able to find solace in this exchange of comparative language, but how effective is it? When I say “effective,” I’m not really referring to the idea that speaking of this situation for what it is may aide us in processing — although it may: this doesn’t feel like heartbreak, it is heartbreak, so why not say so? Instead, I’m referring to the “effectiveness” that seems to be lacking in conversations between people with differing views. On the surface, I’m talking about people that cast their ballots for Trump and people who couldn’t stomach the idea. But, more so, I’m speaking about conversations amongst people with vastly different perceptions of America. Explaining your experience, your concerns and your grief through comparative language may make it more digestible, but is it “effective?”

This brings me back to “Moonlight.” The beauty of the film is that it is highly aware that comparative language fails us. Similes and metaphors are delivered in two parts. The tenor is the subject of comparison; it’s what is being described. The vehicle is that which is used to describe the tenor. The vehicle, though often employed to simply heighten poeticism, is put forth to define a subject in relation to something else. I’m going to stretch these terms a little in talking about “Moonlight,” but bear with me, I haven’t decided if this article is self-reflexive yet…

“Moonlight” abandons the vehicle. The film addresses some considerably heavy subject matter, but it doesn’t do it in a baby-steps manner for the viewer. The film has no intense monologues that I can recall, and the conversations rarely get right at the root of the Chiron’s experience. There aren’t any notably climactic scenes. An example: Juan, a drug dealer (Mahershala Ali) that embodies a temporary father figure for Chiron (this is reductive, but I have a word limit) in “Little” dies. His death, only briefly mentioned when Chiron’s mother remarks that she hasn’t seen Juan’s wife since the funeral, isn’t rendered a narrative peak. All we know is it happened somewhere in the open space between chapter one, “Little” and chapter two “Chiron.” In dealing with the tragedies, for lack of a better word, the film doesn’t grant the viewer a “vehicle” for understanding. We don’t get the tear jerking conversation that we’ve been trained to be sad about. Many of the filmic scenarios that we’ve been trained to associate with sadness are stripped from “Moonlight,” and I’m happy about it. If we’re given a funeral scene, we can relate it back to all other funeral scenes. We think ‘this is sad,’ and leave it at that. There are several reasons why the film’s deconstruction of the fetishization of sadness is meaningful, but I’m most pleased with it because of the resulting openness of the film. We’re not able to swallow the sadness whole through funeral scenes, or heart-to-hearts or diary entries. Rather, it’s left open, asking to be interpreted and re-interpreted by the viewer. Referring to Elizabeth Cowie’s quote of Jill Godmilow in her essay “The ventriloquism of documentary first-person speech and the self-portrait film,” the film prevents viewers from “melt[ing] into pure disembodied spectators.” We’re asked to continuously interpret the film, and think of the implications it has in our own life.

Conversations about the election ought to do the same thing. To relay our perceptions to someone with seemingly opposite perceptions through digestible metaphors allows them to only skim the surface of what is said. We say the election feels like a heartbreak and it resonates with them only momentarily. To effectively relay experience is to open up a realm of poeticism that can never be fully grappled with.

As filmmaker Trinh T. Minh-Ha said in an interview with Nancy Chen, “Truth never yields itself in anything said or shown. One cannot just point a camera at it to catch it: the very effort to do so will kill it.” “Moonlight,” through indispensable scenes featuring subdued dialogue, beautifully placed music and recurring water imagery opens up a void. And it is a void Minh-Ha defines as a space in which “possibilities keep on renewing, hence nothing can be simply classified, arrested and reified.” The film calmly washes over you, but you are left anything but settled. Chiron is bullied, imprisoned, abandoned and betrayed, but the gravity cannot even begin to be felt until you’re walking home from the theater.

This regard for undoing is seen through the film’s self-reflexivity. Each chapter ends before we’re ready for it to, and so the film seems to say, ‘a life can only begin to be understood.’ Additionally, the film’s titles perhaps suggest the dangers of trying to process someone’s identity or experience. “Little” and “Black” are nicknames (and assumed identities) inflicted onto Chiron and to moonlight is to have another job in addition to a ‘regular’ one, suggesting that to “know” an identity is to forget about inherent dualities.

Through the abandoning of digestibility, the film ultimately reminds us that a life is a life. The complexities of said life cannot be bound and thus cannot be understood in a two-hour interval, or in the vehicle of a metaphor.

I haven’t really figured out how to effectively talk about the election, but I’m open to suggestions. “Moonlight” is now showing at Amherst Cinema.

Comments ()