The Secret History of Greek Life at Amherst College

Though fraternities disappeared from Amherst decades ago, the questions they raised about exclusivity, power, and campus culture remain. Staff Writer Isla Howorth ’29 investigates the long, complicated history of Greek life at Amherst — and what traces of it persist.

Greek life has a dominating presence at colleges across the country, shaping everything from social life and housing to philanthropy and campus politics. In 1952, Amherst became the first college to impose a 100% rushing mandate, requiring all enrolled students to join a fraternity. It was not until the 1960s that the college provided living arrangements outside of fraternity houses to upperclassmen. Now, however, it has been more than a decade since Amherst reaffirmed its 1984 decision to abolish fraternities — and nearly as long since Greek life was last written about directly in The Student. So what happened between the establishment of Amherst fraternities and their removal, and what is their legacy today?

Greek life first became available on campus in July 1830, when eight seniors received a charter from Yale to establish an Amherst chapter of the secret society Chi Delta Theta. Unlike fraternities, which would later emerge as publicly recognized social organizations with national affiliations, open membership processes, and visible roles in campus life, secret societies operated with a culture of concealment, restricting knowledge of their membership and rites. Regardless of this distinction, Chi Delta Theta effectively laid the institutional groundwork for a broader fraternity system. Students suddenly had a model for how such organizations could operate — socially, structurally, and symbolically — and future groups followed that template. Six years later, the national fraternity Alpha Delta Phi would open a campus chapter, and from this point onwards, “secret” and “anti-secret” (organizations that opposed the secrecy of fraternities, promoting open discussion and democratic participation) societies at Amherst multiplied.

In 1842, long-uneasy faculty demanded that the secret societies hand over their constitutions and records — a move rooted in concern over unchecked power and lack of transparency — but were refused by the organizations. The societies prized their internal governance and rituals, and relinquishing their documents would have meant surrendering a core part of their identity. The conflict also revealed a fault line in campus life — between student organizations that wanted to self-govern, and faculty who felt responsible for moral and institutional oversight. The societies’ eventual partial accommodation — initiating President Edward Hitchcock and his son, Edward Hitchcock Jr., into Alpha Delta Phi — temporarily eased tensions, but the secrecy itself remained largely intact.

By the mid-20th century, these underlying issues reemerged with new force. Throughout the 1940s and 1950s, the fraternities came under increased fire for their discriminatory membership practices—specifically, the racial and religious exclusions directly written into some national constitutions. As Amherst became one of the many institutions to question whether the discriminatory practices of Greek life were in alignment with its broader educational objectives, the college pressured fraternities to cut ties with the national bodies enforcing such rules. These tensions culminated in the 1970s, when Amherst — formerly a men’s college — became co-educational beginning in the 1975-76 academic year. With women now enrolled as full-time students at Amherst, the campus culture and rigid social hierarchies built upon the foundations of all-male fraternities felt increasingly incompatible with the college’s new mixed-gender student body. The role of Greek life at Amherst was, not for the first time, under contention.

By the early 1980s, the college could no longer reconcile the inherent racial, sexual, and social issues of the fraternities with its broader institutional values, prompting renewed scrutiny of the fraternity system. And so, in 1984, the college decided to abolish fraternities on campus — a decision that came as the result of an investigation by an ad-hoc committee, which reported that “we believe finally that Amherst as a residential college can be better without fraternities than it can be with them.” Terry Allen, the spokesman for the college at the time, said this marked the eighth time the Amherst Board of Trustees had debated dissolving the fraternities since 1945, citing issues related to “antisocial behavior” and “rowdyism.” President Hal Ball said that “even students who did not belong to frats were having their social life decided for them, because people who don't belong to frats still rely on them for their social life.” Student reactions to the abolition were mixed, with a two-and-a-half-day-long hunger strike and the burning of college-related effigies sitting at the most extreme end of the spectrum. However, many students noted that they found even these reactions to be relatively mild and had expected more violent outbursts to occur. It appears that the general consensus on campus was that the Board, despite having met with a council of students, had not made an “adequate effort to solicit student opinion” on the question of fraternities.

Following the ban, many fraternities reconstituted themselves as "underground" — moving off-campus and no longer operating as registered student organizations. Most chapters lost their houses, ceased using Greek letters publicly, and could not advertise events, recruit openly, or register gatherings with the college. Some groups maintained informal ties to national organizations, while others severed those relationships when national bodies required adherence to co-education policies. The underground fraternities continued to exist socially — often as private, off-campus groups — but without the structures, accountability mechanisms, or formal governance that typically accompany official Greek organizations.

Prior issues associated with Greek life carried over into the underground era: Students reported continued hazing, alcohol misconduct, misogyny, and the same tight-knit, exclusive networks that had raised concerns in the first place. Without institutional recognition, however, the college had no direct way to enforce rules or temper the more serious expressions of those problems. One of the most extreme instances of misogynistic behavior occurred in 2012, when Theta Delta Chi (TDX) designed a t-shirt that brought to light the underlying gender prejudices of the fraternities. The scandal — and, more specifically, the college’s cover-up of the scandal — brought to light the rampant issue of underground sexual assault on campus. Indeed, just two years later, a federal investigation of the college for suspected Title IX violations was launched.

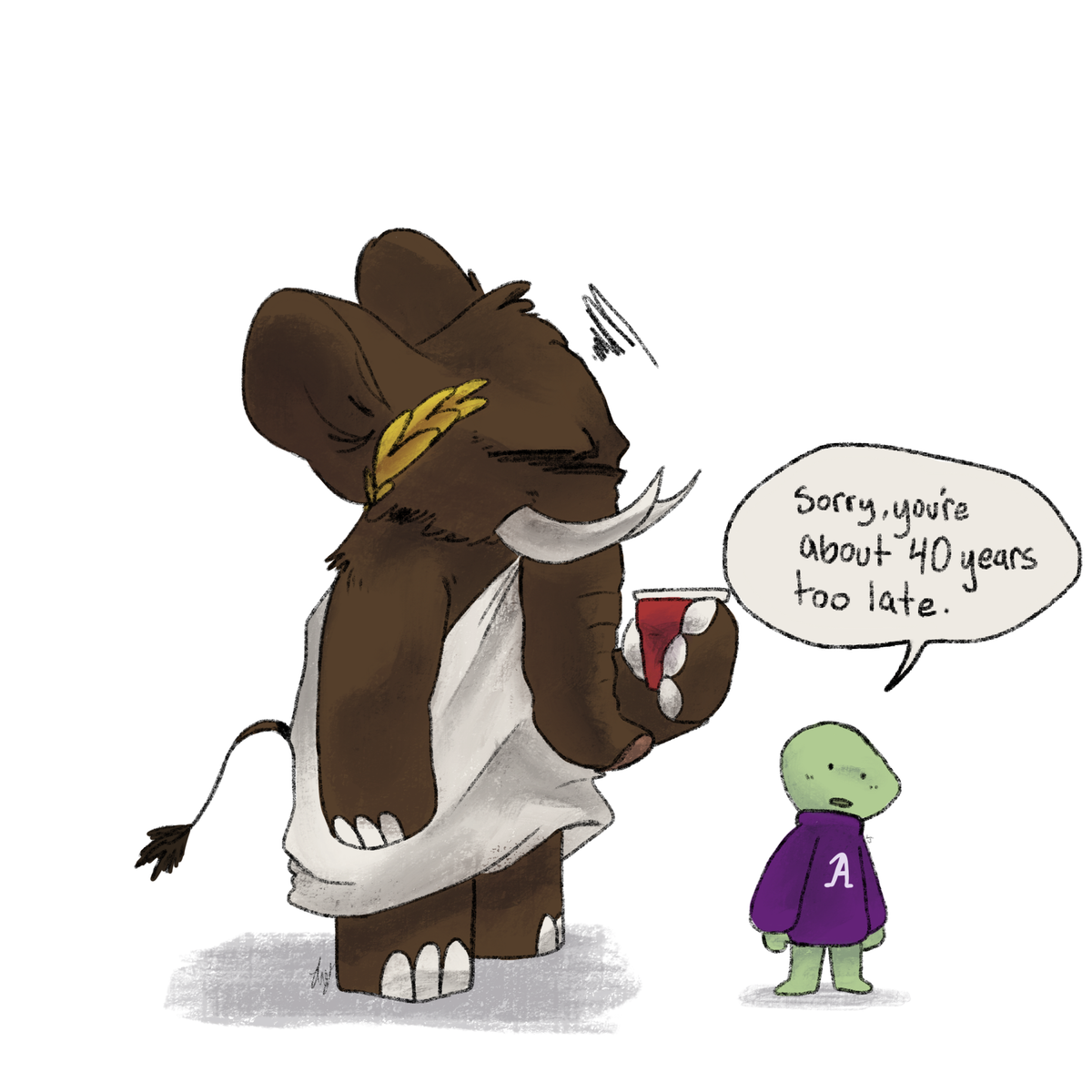

In response to this investigation, and to a 2013 report from the Sexual Misconduct Oversight Committee expressing concern that the underground fraternities’ unofficial status was preventing the college “from enforcing appropriate expectations for student behavior,” the Board of Trustees reaffirmed their decision made 30 years prior to abolish campus Greek life, this time adding a clause to include “fraternity-like and sorority-like groups” in the ban, too. Students took issue, however, with the wording of this clause, stating that there was no clear definition as to what ‘fraternity-like’ meant. As the Editorial Board commented in 2014: “Extracurricular groups and athletic teams may not identify with Greek letters, but that does not mean that they cannot engage in hazing or excessive drinking.” What’s more, many were also deeply suspicious about how the college’s newly-proposed social clubs — framed as a “solution to campus loneliness” — and the underground fraternities that they had just banned were actually different.

So, where does this leave Amherst in 2025? The 2014 reaffirmation of abolition appears to have been largely effective in removing fraternities from campus life — if there are any underground organizations remaining, they are certainly doing a very good job at remaining inconspicuous. Yet Amherst’s long history of Greek life has hardly been erased. You can still feel it in the places the fraternities once called home — in buildings like Charles Drew House or Hitchcock Dormitory — or in the old composites and memorabilia tucked away in the Frost archives. Even though the fraternities themselves are gone, the issues that once surrounded them didn’t simply vanish with the letters on the door. Questions about social exclusivity, gender, race, and who gets to shape campus culture are still very much part of student life here. That’s why this history is worth remembering. It shows how Amherst has wrestled with these tensions before, how students and administrators have tried — and sometimes failed — to create a community that reflects the college’s values. And it reminds us that the debates happening on campus today didn’t appear out of nowhere; they’re part of a much longer story that continues to shape the Amherst we are experiencing today.

Comments ()