The World, Seen: On Beauty and Storytelling

Imagine, for a moment, that for the first time in your Amherst career, you are visiting the Mead Art Museum on your own accord. For some, this will be a fresh memory, while for others such an imaginative feat might be a near impossibility. Imagine that no class brought you to view sketches or still-lives as source materials for a project, no visiting family members brought you along on their touristic explorations of Amherst and the surrounding area and there are no Zumbyes singing among the artwork as you meander the Mead’s galleries. Instead, most of the galleries are empty but for a lone guard or a pre-frosh’s family, and you are exploring alone. Imagine yourself finding a painting that you like. Imagine that this is not just a painting that you like for any reasons at all (such as moral or political reasons, or historical reasons, or reasons of technical adeptness), but a painting that you like because you find it to be beautiful.

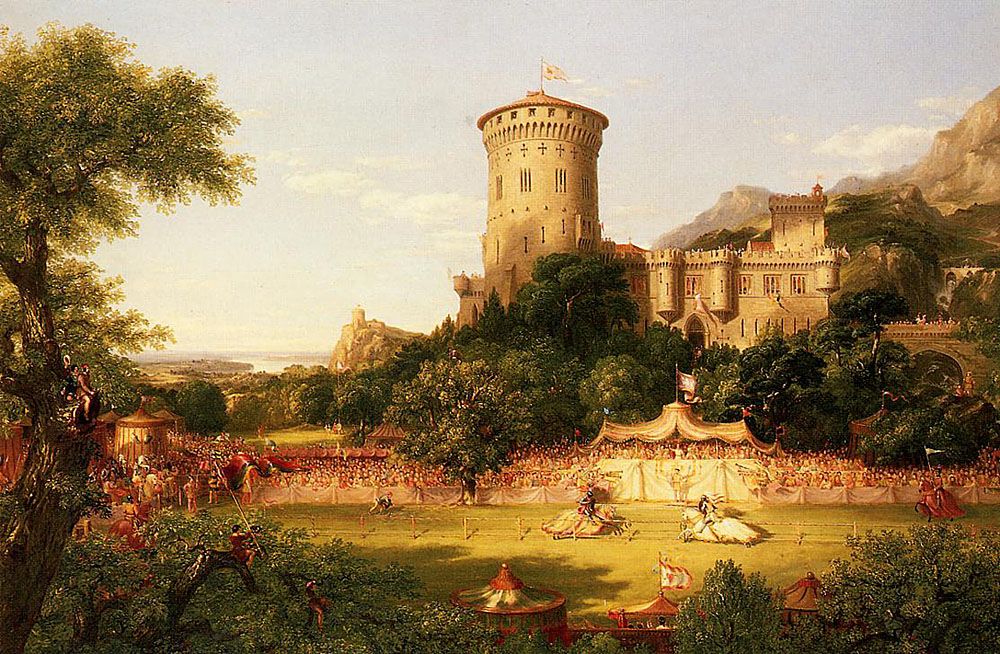

As I undertake this act of imagination, I see Thomas Cole’s “The Past.” Maybe you thought of the same painting. After all, one cannot visit the Mead and miss it, hanging in front of the entrance as it is: the Hudson River scenic background, a castle jutting out of the mountainside and hundreds of ill-defined onlookers watching the near-collision of two jousting knights. Call it lovely, or magical or beautiful (or use an even more antiquated term, like fair or goodly): there is something striking about this painting (and many of the surrounding paintings as well), something that stops you in your tracks and demands your attention. Consider that experience, the experience of that full pause caused by the colors and forms of visual experience. What is that experience like?

In my last column, I turned to the sciences and social sciences to seek answers to that question, arguing that approaches from the mindsets of evolutionary biology, neuroscience and anthropology all answer it in a somewhat insufficient way. Each of those fields enables its practitioners to precisely articulate the state of the physical world such that an experience of beauty occurs (explaining why it is that people come to have such feelings, or pointing to the regions of the brain active when one feels the beauty-feeling), but offers little insight into the experience itself. The experience of beauty feels a certain way and is valued a certain way, and accounts of the state of the world do little to explain those feelings and values.

Consider the approach to conceiving the experience of beauty from a different academic discipline: literature and storytelling. As would be expected, novelists offer a multitude of (often conflicting) accounts of the experience of beauty. Their tools are words, and metaphors, and shared experiences with their readers. Instead of articulating the state of the physical world, novelists describe the experiences of their characters, and often their own similar experiences, by offering vocabulary, unexpected connections, and (sometimes) elaborate interpretation.

Consider Oscar Wilde, who writes in a letter that a “work of art is superbly sterile, and the note of its pleasure is sterility,” describing the beautiful as that experience of objects which is never followed by the desire for “activity of any kind.” “A flower blossoms for its own joy,” he says, and “we gain a moment of joy by looking at it. That is all that is to be said about our relation to flowers.” Here the experience of beauty is joi de vivre, the joy of life itself, paralyzing in its mere vivacity, lasting no more than a moment.

Consider Robert Stone, one of whose protagonists in “A Flag for Sunrise” dives into the ocean and finds an “icy fragile beauty…beyond the competency of any man’s hand, even beyond man’s imagining.” Stone continues in free indirect discourse: “It seemed to him its perfection provoked a recognition. The recognition of what? He wondered. A thing lost or forgotten.” Here beauty demands attention by arousing a recognition of something never known, evoking a memory that does not exist by its stark perfection. It is less a paralyzing joy than a source of amazement, of contemplation, and of reverence for the natural world.

Consider Stephen Dedalus, James Joyce’s celebrated protagonist of “Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man.” Dedalus proclaims, “the instant wherein that supreme quality of beauty, the clear radiance of the esthetic image, is apprehended luminously by the mind which has been arrested by [the artwork’s] wholeness and fascinated by its harmony is the luminous silent stasis of esthetic pleasure.” Hidden in this cryptic language is a description of my experience of Thomas Cole’s painting. Joyce associates that experience with a spontaneous “luminosity” of the mind, as if the experience of beauty were comparable to the long-sought grasping of a deep societal concern, or of a mathematical proof.

Finally, consider Yann Martel’s Life of Pi, either in the form of last decade’s book or this decade’s film. Here is one way to state the moral of Martel’s story in one sentence: there is much about the world that can only be explained through a story. Martel wrote the story with what President Barack Obama has called “an elegant proof of God” in mind, but his story’s implications extend to human experience alongside the existence of the supernatural. The experience of a painting at the Mead can be characterized by the scientist in innumerable ways, but every one of those ways will miss Wilde’s joy or Stone’s recognition or Joyce’s luminosity. An explanation of the experience of beauty calls for the participation of the scientist and the humanist both.

Comments ()